Starting in the mid-1980s, Father Gregory Boyle, a Jesuit priest, rode his bicycle in East Los Angeles’ Pico Gardens and Aliso Village public housing projects to preach about religion, kinship and hope to the homeboys and homegirls (homies). Despite being an outsider, white, middle-class, educated, in these notorious projects—once he gained the confianza of the residents and homies—Father Boyle gradually became accepted in these predominantly Chicana/o neighborhoods. For many decades, before being demolished by the capitalist state, these projects were plagued by abject poverty, violence, police, gangs, systemic racism and hopelessness.

By understanding the codes of conduct on the mean streets of East Los Angeles and adopting the local vernacular without judgment, the Jesuit priest transformed from Father Boyle into “Father G,” “G” and “G-Dog.” As someone who grew up in East Los Angeles’ Ramona Gardens public housing project, I intuitively know what it takes for an outsider to be accepted in a place where confianza is hard to come by. As a trusted outsider, Father Boyle won’t violate the unwritten rules of the streets, such as informing, or snitching, on the homies to the cops. In 1990, for instance, when the late Chris Wallace of 60 Minutes interviewed Father Boyle and questioned him about his close connections or loyalties with the homies vis-à-vis the LAPD, the Jesuit priest responded without apologies or equivocation: “’I didn’t take my vows to the LAPD.’” This is an important lesson for outsiders, especially when seeking to understand or attempting to “help” the most vulnerable among us in America’s barrios.

In 1992, after working with residents and staff to help the homies to secure employment through a non-profit, Jobs for a Future (JJF), Father Boyle founded Homeboy Industries. While Father Boyle deservedly gets credit for founding Homeboy Industries, any successful organization requires the collective work of many individuals who believe in the mission of the organization, especially for progressive non-profits or social enterprises. As the mottos of the embryonic Homeboy Industries included “Jobs Not Jails” and “Nothing stops a bullet like a job,” this gang rehabilitation and re-entry program initially started with a few social enterprises to provide viable employment opportunities for marginalized individuals who were/are regularly blocked from the racist labor market. This includes Homeboy Bakery, Homeboy Silkscreen, Homeboy Graffiti Removal Services, Homeboy Maintenance Service and Homeboy Merchandise.

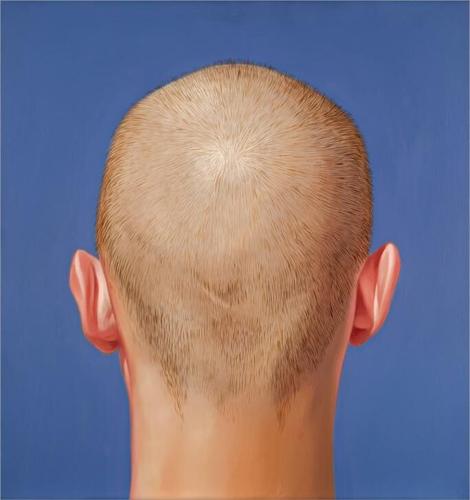

“Untitled,” back of head, 12″ x 11″, Salomón Huerta (1999)

Over the years, Homeboy Industries has experienced failures and successes, from an unstable non-profit on the brink of closure to a highly successful organization with expanded services and self-sustainable social enterprises. According to its official website, it has a major impact not only in Los Angeles, but also the world: “Homeboy Industries is the largest gang rehabilitation and re-entry program in the world. For over 30 years, we have stood as a beacon of hope in Los Angeles to provide training and support to formerly gang-involved and previously incarcerated people, allowing them to redirect their lives and become contributing members of our community.”

In addition to the expanded services and social enterprises aimed at homeboys and homegirls in the greater Los Angeles area, Father Boyle has dedicated his life to humanize the demonized, give unconditional love to the rejected, and “accompany those on the margins.” Apart from his work at Homeboy Industries, he does so in the form of his sermons and speeches at churches, juvenile halls, non-profits, universities and other venues. He’s also engaged with TEDx talks and social media platforms. This also includes his writings in the forms of articles and brilliant books.

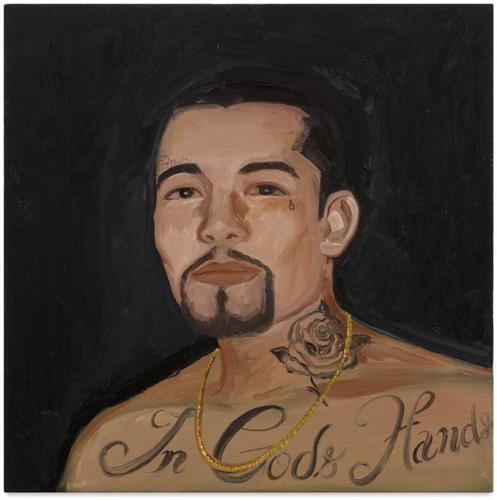

“In Gods Hands,” oil on canvas, 14″x14″, Salomón Huerta (2023)

In his New York Times best seller book, Tattoos of the Heart (2010), Father Boyle writes a chapter on kinship. “Mother Teresa,” he eloquently posits, “diagnosed the world’s ill in this way: we’ve just ‘forgotten that we belong to each other.’” Elaborating on this theme, he writes: “Kinship is what happens to us when we refuse to let that happen. With kinship as the goal, other essential things fall into place; without it, no justice, not peace. I suspect that where kinship our goal, we would not longer be promoting justice—we would be celebrating it.” In this quote and throughout this insightful book, Father Boyle sheds light on what’s missing in American society. Instead of uniting as human beings, American leaders often seek to divide us based on our race/ethnicity, class, gender and sexual orientation. This is especially the case with conservatives. Instead of kinship, in mainstream American society and politics, it’s often “us-versus-them.” White versus black. Rich versus working-class. Citizen versus immigrant. In the case of Brown people in white America, we are usually the “them.”

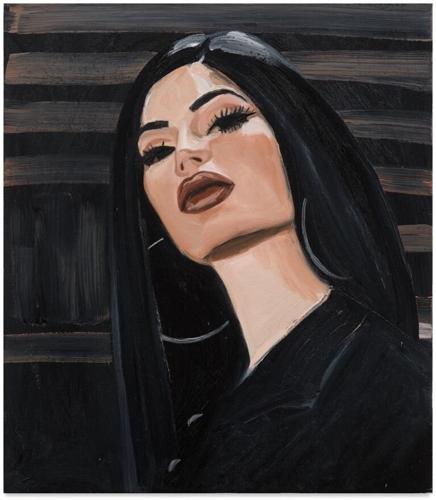

“Yvette,” oil on canvas, 16″x14″, Salomón Huerta (2023)

Whenever Father Boyle speaks in public, he tells moving stories of the homies he’s met and helped over the years, including those whom he has buried. In his compassionate stories, he not only teaches us about the abuse and trauma that these human beings, not gang members, have gone through in America’s barrios, but also about how many of them have transformed their lives for the better because of Homeboy Industries and beyond. Speaking of those on the margins, two words come to mind that American leaders and citizens/residents should learn from: compassion and redemption.

Hector Verdugo is a fine example of compassion and redemption. Like me, Hector grew up in East Los Angeles. While we both experienced/witnessed poverty and violence, he experienced both at a deeper and higher level compared to me. Same hazardous place, [but] divergent outcomes. In Hector’s case, his life (accompanied by his twin) was plagued by poverty, violence (inside and outside the home), drugs, police abuse, incarceration and hopelessness. Many years later, seeking a way out of the vida loca (not the fake Ricky Martin version), he found compassion and redemption at Homeboy Industries. After dedicating many years to Homeboy Industries in different capacities, he was promoted to Associate Executive Director. Like Father Boyle, he’s changing the world one … homie at a time.

On February 10, 2016, as part of his awardee lecture for the 2016 Dale Prize at my campus, Hector delivered a heartbreaking and heartwarming talk. Speaking candidly and openly about the brutal hardships he experienced (along with his twin) in East Los Angeles and the prison industrial complex, he also sheds light on the pain and harsh realities that many homies experience. In speaking about the power of Homeboy Industries, he said: “We learn to transform our pain.” He also spoke about the importance of creating caring communities: “The most important thing we do at Homeboy’s is we’re a loving community, a loving environment that helps people heal from their traumas.”

It behooves us, as a society, to be in solidarity with those who have been abused by racial capitalism. To end the production and reproduction of abuse and hopelessness in America’s barrios, we must focus on the causes of oppression versus symptoms or manifestations.

“Untitled,” homegirl, oil on canvas, 19”x17”, Salomón Huerta (2021)

My solidarity with the homies is both academic and personal. On an academic level, I seek to investigate the root causes that create gangs in America’s barrios, from redlining to housing segregation; from systemic racism to anti-Mexicanism. I seek to do so without glorifying or romanticizing gangs or gang members. At a public policy level, I seek to end Brown on Brown violence. Too many of my childhood friends were killed or shot by other marginalized Chicanos who look like them. Seeing their mothers cry breaks my heart.

On a personal level, as noted above, I grew up in a neighborhood deeply embedded with gang culture. It was/is hegemonic in the projects. My familia wasn’t immune. (I always joke that “my gang application” would’ve been rejected since I was too thin to defend the neighborhood.) My siblings and I experienced/witnessed violence regularly. It was a dark cloud that followed us—in and outside of the projects. A homeboy once pointed a gun at my brother Salomón (the acclaimed artist whose work is included here). He was returning home late at night from Art Center College of Design. “Sorry, bro,” the homeboy said, “I thought you were someone else.” Two of my sisters were shot outside of the projects, for instance. There are other dark stories that I would never share to avoid breaking the street code. That said, we didn’t live in fear in the projects since we were childhood friends with the homeboys.

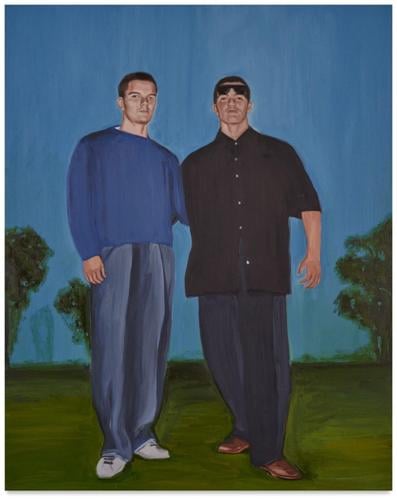

"Untitled," twins, 35"x28", Salomón Huerta (2022)

Apart from the neighborhood gang and its cliques, there were/are three other gangs that rule(d) the projects. One was/is the Housing Authority. The surveillance was/is omnipresent. They treat(ed) us like wards of the state. Big Brother. The other gang was/is the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s. The same ones that killed Arturo “Smokey” Jimenez on August 3, 1991, along with many more homies. There’s also the feared LAPD. When I was 16 years old, for instance, a cop pulled a gun on me. My crime? I made a rolling stop while teaching myself how to drive my ’67 Ford Mustang that my sister Catalina gifted me. Throughout East Los Angeles, police abuse against Brown people continues to the present.

When privileged Americans (and others) judge the homies for their conduct or dress code, etc., why are they not being critical of the gangsters in government and their abusive agents?

In closing, instead of judging and being critical of those on the margins, Americans and their leaders should embrace kinship, confianza, compassion and redemption, as modeled by the leaders and members of Homeboy Industries in service of los de abajo.

(0) comments

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

Keep it Clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexually-oriented language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't Threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be Truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be Nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be Proactive. Use the 'Report' link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with Us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.