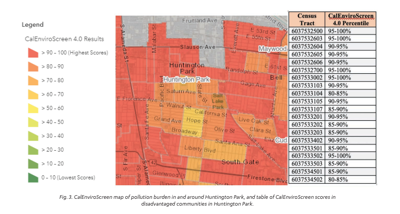

Current pollution exposure in Huntington Park (UCLA Emmet Institute - 2023)

In Louisiana, there is a corridor of cities that is called “Cancer Alley,” where for several generations communities of mostly Black residents have suffered health defects and cancer cases that do not seem to decrease.

“There's no such name for the corridor that stretches from East L.A. down along the 110 and 710 Freeways all the way to Wilmington and Long Beach and San Pedro,” said Manuel Pastor PhD, USC Director of the Equity Research Institute. said. “But there ought to be because this is one of the most polluted areas in Southern California.”

As growing attention, funding and support has come to this region, the long-fought campaign for environmental justice continues.

In 1994, the Northridge earthquake caused the Santa Monica Freeway to collapse completely. The cleanup operation resulted in a massive pile of concrete debris being dumped in Huntington Park with little to no input from the residents.

The demographics then closely mirror today’s: Huntington Park is currently home to 53,000 people, with over 97% of that population being Hispanic or Latinx.

Now, a school stands in Huntington Park named Linda Esperanza Marquez High School, honoring the local leader who helped rid the community of “La Montaña,” a pile of rubble that expanded over 200,000 tons. The school is a reminder of the coalition and leadership it took to get rid of the debris, with reports of children requiring medical attention due to intense dust exposure. Residents mobilized, demanded accountability and forced the city and county to act, proving that community-led organizing was key to addressing environmental injustices.

With the latest data and legacy of organizing, there is more evidence of resistance that was met with rejection by city and county leaders. As white flight resulted in white affluent residents moving out of cities like Huntington Park and Latin American immigrants found jobs and housing, making South East Los Angeles their home, the city councils and leadership remained white during the 1990s and 80s.

As social scientist Laura Pulido PhD wrote in 2000’s seminal essay “Rethinking Environmental Racism”, “Immigrants do not settle just anywhere, however. Their decisions are informed by the geography of past racial regimes. As a result, central Los Angeles continues to be a nonwhite space.”

Systemic barriers to cleanups

While there have been strides and recent efforts to ensure a clean up takes place in the city of Vernon, the Trump administration has already begun its overhaul of EPA services, which includes cutting funding and reducing oversight for environmental justice programs. The Superfund program, meant to remediate highly contaminated sites, saw delays in cleanups as the administration deprioritized regulations that were meant to hold polluters accountable.

According to an AP report, Trump-era policies slowed environmental cleanups nationwide, including those in predominantly Latino and Black communities. This included weakening enforcement against corporate polluters and reducing penalties for environmental violations, making it more difficult for affected communities to receive justice.

Dr. Pastor notes that in his decades-long work around community-engaged scholarship in and about South East Los Angeles, the region is “highly fragmented.”

“The pollution issues don't stop where the border of Huntington Park becomes Bell or Bell Gardens, or where it's shipped from city territory to an incorporated county territory. One big barrier is trying to get the entire region to speak as one,” he said.

The Los Angeles County Department of Public Health and the Department of Toxic and Substance Control (DTSC) confirmed that the impact area spreads at least 1.25 to 1.75 miles from pollution sites. This means that environmental hazards in one city inevitably spill over into neighboring communities, yet each must fight separately for action and resources.

Regional inaction and grassroots leadership

Although advocacy groups like East Yard Communities for Environmental Justice (EYCEJ) have been successful in building coalitions, the response by electeds hasn’t been noteworthy. While the county has begun initiatives and launched programs to address environmental racism, it has not directly recognized South East Los Angeles as a distinct environmental justice priority zone.

Grassroots organizations such as EYCEJ and Communities for a Better Environment (CBE) have been leading the charge. EYCEJ, founded in 2001, has empowered residents to fight for better air quality and public health protections, particularly in the face of industrial pollution. CBE, through its Youth for Environmental Justice program, has mobilized young people to demand stronger enforcement of environmental laws and greater accountability from polluting industries.

Despite these efforts, the burden of advocacy largely falls on residents and local activists rather than systemic, government-driven interventions. This disparity is compounded by ongoing industrial expansion in SELA, where warehouses, refineries, and manufacturing plants continue to grow without adequate regulation or community input.

Looking ahead: challenges and opportunities

The denial of science has been a persistent obstacle in environmental justice work. “The denial of science around public health showing that these patterns of excess pollution trigger asthma, create problems for student learning, and create public health issues, and the denial of climate change and its impacts in the communities that you're talking about. So I think it's a very troubling time because it's not just that justice is being ignored, it's that facts are being ignored,” Dr. Pastor says.

The Biden administration reinstated some environmental protections, but much of the damage caused by deregulation remains. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has renewed commitments to cleanups, but for communities in SELA, action remains slow and the enforcement of environmental laws is often insufficient.

Scholars like Drs. Pastor and Pulido have articulated for decades that state and county officials are able to do more than acknowledge the problem; they can actively work to designate SELA as a high-priority environmental justice region, ensuring access to funding and resources necessary for large-scale remediation efforts.

In the meantime, the residents of South East Los Angeles will continue fighting for clean air, clean water, and a safe environment—just as they have for decades.

(0) comments

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

Keep it Clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexually-oriented language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't Threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be Truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be Nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be Proactive. Use the 'Report' link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with Us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.