Latinos in the United States have a rich and diverse cultural identity that is marked by various elements such as food, traditions, music and language. Spanish, in particular, plays a significant role in their identity as it is the most commonly spoken non-English language in the country. According to recent estimates, nearly 40 million Latinos in the U.S. speak Spanish at home, reflecting the importance of this language in their daily lives and communities. The use of Spanish in various settings, including social, educational and professional, is a testament to its enduring role in shaping the Latino identity in America.

In recent years, there has been a noticeable rise in the number of individuals within the Latino community who are unable to speak Spanish fluently. This particular group is sometimes referred to as the "No Sabo" generation. Being labeled as a "No Sabo" child or adult, however, can carry a certain degree of stigma within the Latino community since many individuals take great pride in being connected to their Spanish heritage. According to The Pew Research Center, approximately 24% of all Latino adults claim not to be able to carry a conversation in Spanish well, or not at all.

The trend of “No Sabo” adults is a result of anti-Latino discrimination that many previous generations experienced. For decades, the California school systems, along with other states, segregated Mexican American students. During the 1940s, a significant number of students of Mexican descent in California were forced into segregated schools that were poorly maintained and lacked resources. These schools prioritized “working skills” over academic subjects. This discriminatory practice severely limited educational opportunities for Mexican American students, perpetuating systemic inequality and hindering their social and economic mobility.

Stephanie Martinez, a fifth-generation Chicana, revealed to CALÓ News that her grandmother made a deliberate choice not to teach her mother Spanish. Martinez explained that her family identifies as "truly Mexican American," and shared that her great-grandparents were migrant workers who would "follow the crops." This term is used to describe farmworkers who traveled from state to state, working on different crops as the seasons changed.

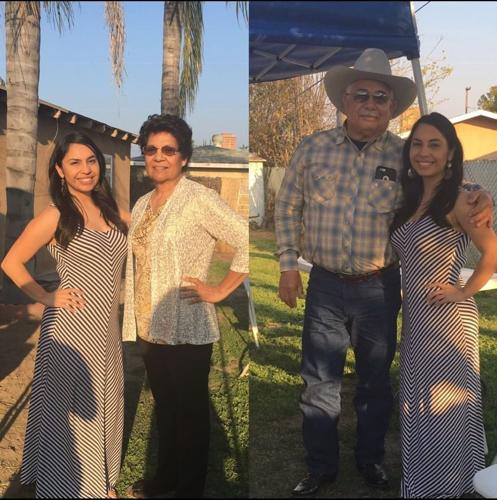

Martinez with her grandmother and grandfather. Image credit: Stephanie Martinez

As she grew older and began to ask more questions about her heritage, Martinez said her grandmother would often get emotional when recalling her experiences in the public school system. “When she was in elementary school my grandmother and other migrant students had to take classes in the janitor's closet,” said Martinez “They weren't allowed to be with the other students,” Martinez said her grandmother also remembers various instances in which immigrant students would get locked in the utility storage simply for speaking Spanish, which is part of the reason she dropped out after fifth grade.

Martinez’s grandmother isn’t alone in her experience, many children of immigrants, and migrant youth grew up fearing the consequences of speaking Spanish or showing any hint of an accent in a xenophobic society. The prejudice that Latino-American communities experienced, led to negative stereotypes and violence, especially for those of indigenous descent.

The experience of Latinos like Martinez's grandmother is a poignant reminder of the struggles that many immigrants and their descendants have faced. It also sheds light on why younger generations lack Spanish fluency.

However, many Latinos have rejected the “No Sabo” title, as it often carries a negative connotation. “I don’t like the term,” says Nathaly Gamino, a Long Beach resident, who was originally born and raised in Chicago. “I think that everybody has very different experiences,” she said to CALÓ News. “For example, people in California have a very different experience being Latino and speaking Spanish than people in Chicago [Illinois] or Texas did.”

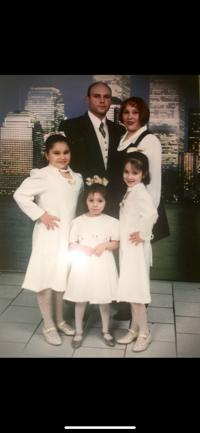

Nathaly Gamino poses with two of her sisters, her mother and step dad. Image Credit: Nathaly Gamino

Gamino grew up as a child of immigrants, but her parents separated when she was young. Her biological father was the primary Spanish speaker at home, but after he left when she was five, Gamino was raised by her Mexican mother and Cuban stepfather. From the age of five to 18, she lived in a three-story apartment building in Chicago with other multi-generational families. Although her parents spoke perfect English, her household was diverse and included people from different generations.

Unlike Martinez, Gamino did not move to California until adulthood. As a result, she has a unique perspective on staying connected to her roots, particularly growing up in a Mexican neighborhood in the Midwest. “I feel like I connected with Spanish through music and the arts,” says Gamino who recalls going to the National Museum of Mexican Art when she was little and listening to Selena. “Selena was a ‘No Sabo’ herself, so I was like I love this girl–she is me and I am her!”

Gamino and her mother. Image credit: Nathaly Gamino

Due to distance and circumstantial factors, Gamino also did not experience traveling to Mexico growing up. “I'm comfortable saying this now, but most of my life, my mom was still undocumented.” Gamino’s experiences as the daughter of undocumented immigrants is not an uncommon one. The Pew Research Center estimates the undocumented population was 10.5 million in 2021. Many Latino Americans grow up in multigenerational households, but not all have the opportunity to travel back and forth across the border due to their family's immigration status.

Still, Gamino’s inability to speak fluent Spanish does not make her feel any less connected to her roots or culture. Research indicates that approximately 75% of U.S. Latinos report being able to carry on a conversation in Spanish “pretty well or very well,” only 34% of third- or higher-generation Latinos say they can carry on a Spanish-language conversation at least pretty well, with only 14% saying they can do so very well.

Although she continues to work on her fluency for personal and professional reasons, Gamino strives to dispel the “No Sabo” label and highlight the diversity of Latinos in the U.S. “I want to make sure that Latinos like me are being represented, even those that don't speak Spanish,” she said.

(0) comments

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

Keep it Clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexually-oriented language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't Threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be Truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be Nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be Proactive. Use the 'Report' link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with Us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.