The Dodger Stadium stands on top of what once was Bishop, La Loma and Palo Verde. Photo by Joel Muniz

The Dodgers’ loud silence regarding the immigration raids and mass deportation in Los Angeles is not the first time the organization has shown that it has no backbone.

It took two weeks and daily ongoing pressure from the community for the Dodgers to talk about the raids and announce their very disappointing $1 million monetary donation for immigrant families affected by the raids.

The Los Angeles Dodgers, whose current net worth is valued at $7.73 billion, according to a March 2025 valuation by SportsPro, have increased by 23% in value compared to the previous year. The team's highest-paid player, Shohei Ohtani, has a 10-year, $700 million contract, averaging $70 million per year. Mookie Betts is their second-highest-paid player, averaging $30 million per year.

Despite this, the institution’s donation to the California Community Foundation’s L.A. Neighbors Support Fund and other organizations in response to the raids that have affected the city they have lived in, benefited from and extracted from lacks moral fiber, not just because of the absurd quantity but because of their lack of courage to do more, locally and nationally.

But this isn’t the first time the Dodgers have let down the Latino community. The team's lack of courage and the inability to take a stand and support efforts that are on the road to justice is a prevalent pattern and it doesn't take long to find another recent example of this.

Only a year ago, in the spring of 2024, a bill known as the Chavez Ravine Accountability Act or AB 1950, was introduced in the California Legislature. The bill sought to provide reparations, compensation and accountability for the hundreds of families, mostly Mexican American, who were displaced in the 1950s and 1960s from the La Loma, Bishop and Palo Verde neighborhoods, the area now known as Chavez Ravine, where Dodger Stadium currently sits on top of.

A general view of Dodger stadium, an area where street vendors are no longer banned from selling per city ordinance. (Harry How/Getty Images)

Although the bill was vetoed by Governor Gavin Newsom that fall, citing that the efforts to address the injustice that took place in that community should be established at the local level instead of at the state level, the Dodgers never publicly said anything regarding AB 1950 or the Chavez Ravine community. For six months, from when the bill was introduced until it died on the governor's desk, nothing was ever said by the organization either in support or opposition.

Many people, however, think it is ridiculous to expect the Dodgers to stand up against police brutality and the eviction and abduction of local residents and foreigners, given that the team and its franchise were founded on the basis of these injustices. For many, the team has never been a true ally to the working-class people of Los Angeles, and this can be seen in the very first years that the Dodgers came to L.A.

Before the Dodgers Stadium was constructed, La Loma, Palo Verde and Bishop intertwined to form the 315-acre area, a valley a few miles northeast of downtown L.A., home to more than 1,800 families.

Despite the perspectives of outsiders and the City of Los Angeles officials, who often labeled the community as a “vacant shantytown” or the “slums,” the three neighborhoods were fully autonomous, vibrant and cohesive, serving as a hub for homeownership and economic development and growth for people of color.

The peace and autonomy of those who lived in these neighborhoods came to a halt when the Federal Housing Act of 1949 reduced housing costs, raised housing standards and granted money to cities from the federal government to “clear slums and rebuild blighted areas,” as stated in the act.

The act would expedite the plan for a public housing project, Elysian Park Heights, which was mapped out to include more than 1,000 units—two dozen 13-story buildings and 160 two-story townhouses—as well as several new schools and playgrounds. But a year later, residents received letters from the city informing them that, in order for the land to become available for the plan, they would need to sell their homes. They were also told that those displaced could live in the new housing.

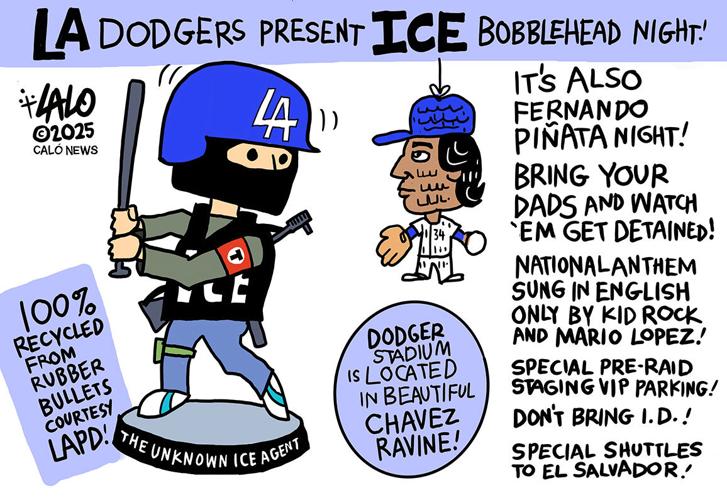

The L.A. Dodgers are not doing a good job backing up why they seem to support the current ICE mass deportation kidnapping raids happening to our community. Ever been to a Dodger game? About half of the fans there appear to be Latino, and especially Mexican American. Well, since the Dodgers actually do a good job hosting Cultural Heritage nights, maybe they should just go full fash and support ICE Bobblehead night! Don't bring your ID!

While many families initially resisted abandoning their homes, by offering immediate cash payments, using the power of eminent domain, or lowballing, the majority of residents were moved out by 1953, when the project fell through.

After the city bought back the land for the promise of public use, only a handful of families still remained in the area, until the Dodgers came.

In June 1958, a referendum was approved to trade the land to the then-Brooklyn Dodgers owner, Walter O’Malley, and on May 9, 1959, residents were forcibly evicted by sheriff deputies, their residences bulldozed.

The violent uprooting and displacement of these families forced more than 1,800 families from their homes and businesses.

Many working-class Latinos were forcibly taken out of their homes to give shelter to the Dodgers, an entity that, more than 65 years later, would turn their back on them again.

The displacement replaced a once tight-knit community with the legendary baseball stadium Angelenos are so fond of today, leaving a lasting impact on the livelihoods of the displaced families and generations that followed.

Vincent Montalvo told CALÓ News last year that the people of these three communities were running their own church, elementary and grocery store.

As a kid, Montalvo said he grew up hearing stories about residents from La Loma, Palo Verde and Bishop who grew their own food and raised animals such as pigs, goats and turkeys, while those on the outside looked at the community as an eyesore.

Montalvo’s grandmother, grandfather, and mother were all born and raised in Palo Verde.

“When I used to listen to my grandfather's stories about the way everyone in those communities cared for each other, I'd tell him it sounded like a beautiful fantasy,” he said. “He would tell me stories about people who used to go play up in Elysian Park, and there were avocado trees, and people would go sit up there and eat, cook together and help each other with the maintenance of their homes and today that sounds so surreal.”

Communities of Palo Verde, La Loma and Bishop that were home to mostly Mexican American fight for reparations for families and people who were displaced from their homes for the development of Dodger stadium in the 1950s.

When CALÓ News spoke to Buried Under the Blue last September regarding the Chavez Ravine Accountability Act, they emphasized the importance of holding the Dodgers accountable.

For the organization, the bill was missing the names of the responsible parties, such as the Dodgers, who facilitated or were complicit in the removal of hundreds of families in the area. Throughout the bill’s text, the Dodgers were referred to as a “sports stadium and an entity.”

Today, Buried Under the Blue says the shortcoming of the team did not begin when they remained quiet, but instead it began the moment they began to profit from land that “was stolen.”

“As ICE targets undocumented families in neighborhoods across Los Angeles, we see history repeating itself: fear, evictions, police violence. And once again, the Dodgers—who profit from land that was stolen—are only speaking up because of public pressure,” the organization stated. “If they truly want to make things right, they must start at the root of their violence—with the people they displaced. The Dodgers have a choice: continue the pattern of erasure or finally begin the work of repair.”

Regarding the $1 million donation, the Dodgers said they will make additional announcements with local community and labor organizations, including the California Community Foundation and the Los Angeles County Federation of Labor, who will receive these funds.

For some, the Dodgers' betrayal is new and heartbreaking, but in reality, the organization has never been in support of the people. Their lack of moral compass has always been there, just well hidden under the heritage nights and Latino-inspired merch.

EDITOR'S NOTE: According to Melissa Arechiga, Vincent Montalvo is no longer a part of the Buried Under the Blue organization.

(0) comments

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

Keep it Clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexually-oriented language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't Threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be Truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be Nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be Proactive. Use the 'Report' link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with Us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.