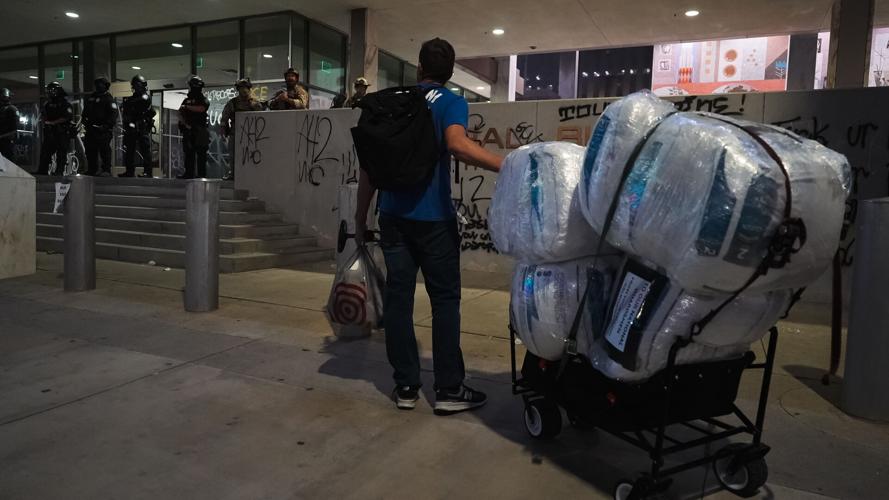

Jack Walsh delivers pillows to National Guard troops based in a Los Angeles federal building. (Photo by Susana Canales Barrón)

Standing at the edge of a demonstration in East Los Angeles—just a day after protesters were tear-gassed and struck by rubber bullets—Elizabeth, an East Los Angeles resident, held a teddy bear dressed in a miniature Marine Corps uniform. Her voice trembled as she told CALÓ News that all three of her children currently serve in the U.S. military: two sons in the U.S. Marine Reserves and a daughter serving as an active duty Marine.

All three have pledged to defy any order that would send them into their own communities to suppress protests or participate in raids.

"They are prepared to say ‘no.’"

To Elizabeth, the boundary between soldier and civilian, protester and detainee, is anything but clear. She believes the government is asking service members to turn against the very communities they come from. For those in uniform with mixed-status families, the consequences are agonizing: follow orders and risk aiding in the deportation of loved ones and neighbors.

Elizabeth, whose children serve in the military, joins a protest in East Los Angeles against Trump-era immigration policies. (Photo by Susana Canales Barrón)

"I've been here since I was five," she said, shaking with disbelief. "It took me 25 years to get my documentation—because I'm Mexican."

That wait, she explained, was marked by fear and precarity, by a constant calculation of the risk of being deported. Now, with her children in uniform, she's haunted by the possibility that they could be used as instruments of the system she spent decades trying to survive. It's a betrayal she can't accept and one that her children have vowed not to participate in.

For military personnel to preemptively refuse domestic orders is extraordinarily rare in recent history. While there are legal pathways for conscientious objection, public declarations—especially during an active federal deployment—are nearly unheard of, especially since the data is seldom published.

That this resistance comes from Latino service members from a family with deep ties to both immigrant and military identity raises critical questions about loyalty, legitimacy and the blurred line between service and subjugation. For soldiers with mixed-status families, the risk of being ordered to detain or intimidate loved ones is no longer hypothetical—it's personal.

A member of the military uses his gear as a pillow as he sleeps on the ground. (Photo by Susana Canales Barrón)

The contradiction deepens further when considering that non-citizens also serve in the U.S. military. Some have been detained or deported despite their service. ICE does not track deported veterans, but legal advocates have documented hundreds of such cases, believed to be only a fraction of the real number.

In Oxnard, where military vehicles and federal agents have grown more visible in recent days, some of the most striking images have come from the community's youngest members. At a recent demonstration, a child arrived dressed in military fatigues. A parent at the rally told CALÓ News that the outfit does not express patriotism but protest.

The generation most impacted by raids, removals and militarized immigration policy is no longer content to remain silent. For some, the uniform no longer belongs solely to the military but serves as a visual counter-narrative, a reminder that those on the receiving end of government power are watching and preparing to push back.

Anayeli Díaz pictured at her graduation from Hueneme High School. Photo courtesy of Anayeli Díaz.

"The children are the brave ones fighting for their parents' rights," said Anayeli Díaz, her voice steady with conviction. A recent graduate of Hueneme High School, Díaz was one of the student organizers behind the early protests in Oxnard, sparked by the first wave of ICE raids during the Trump administration.

For Díaz and her peers, organizing wasn't a choice—it was an inheritance. Many had grown up watching deportations tear through their communities. But instead of retreating into fear, they stepped forward. Young and largely overlooked, they became their families' first line of defense.

"I was separated from my parents when I was six months old because of unjust immigration policies," Díaz said, adding that her older siblings had to take care of her.

The narrative of who is currently in charge has also shifted for Los Angeles resident Jack Walsh, who was stunned when he first saw the images of young troops sleeping on a downtown loading dock in a federal building.

"I brought about 34 pillows for the National Guard," Walsh said. "I'm ashamed—as an Angeleno, as a Californian, as an American. We don't treat service members like this."

Navigating a squeaky-wheeled cart filled with pillows through downtown barricades and police checkpoints, he donated the pillows to the National Guard troops at the Federal Building at 300 North Los Angeles Street, where they had been stationed for days.

A mother stands with her son who is dressed in military fatigues. (Photo by Susana Canales Barrón)

Walsh returned the next day with more pillows, purchased using funds raised from friends and family.

"We're supposed to be the military that flies celebrities to the middle of nowhere in the war zones to cheer troops up, and now we can't even feed them, we can't even get real hotel rooms," Walsh told CALÓ News.

Across the country, scenes like this have become disturbingly routine. In Washington, D.C., troops tasked with securing the Capitol were famously ordered to sleep in parking garages. In Texas, National Guard members deployed to the southern border have been found living in inadequate trailers and lacking other essential resources. Officials routinely describe these conditions as "temporary" or "in transition."

But those improvements rarely come.

On the same day President Trump’s military parade — a spectacle that cost approximately $45 million — rolled through the streets of Washington, D.C., uniformed service members slept on the bare concrete floors of a federal building in downtown Los Angeles. Some clutched their rifles while resting; others used backpacks as makeshift pillows. For the soldiers sleeping on federal floors that night, the price of that parade wasn’t just $45 million. It was dignity deferred.

Jack Walsh delivers pillows to National Guard troops based in a Los Angeles federal building. (Photo by Susana Canales Barrón)

For Walsh, it's not just a failure of planning—it's a failure of conscience. Days earlier, he had attended a protest at an ICE processing center. "I would've brought supplies there, too," he said.

"But I know they're not letting anything in. They're treating people like animals," he said.

In his view, the government's inability—or unwillingness—to provide for those in its charge reflects something deeper than mere dysfunction. It reveals a system that has normalized neglect.

"I have a fourth child who is getting ready to serve as a paramedic," said Elizabeth, originally from Baja California. "They want peace like everyone else."

(0) comments

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

Keep it Clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexually-oriented language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't Threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be Truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be Nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be Proactive. Use the 'Report' link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with Us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.