Social media, WhatsApp, and text messages have become some of the only ways community members across Southern California have been able to document, alert and prepare for the latest ICE raids targeting the immigrant population.

A week into these raids, it has become a necessity for families and immigrants themselves to keep track of where not to go and where potential targets are. What has become a rapidly growing habit and skill, people of all ages in mixed-status families have been urgently learning media literacy. What is accurate? What is new and old? And what information do people need to make decisions?

There are currently two leading platforms where families, allies, and immigrants can look through maps, gather updates and see which ICE sightings are verified or not.

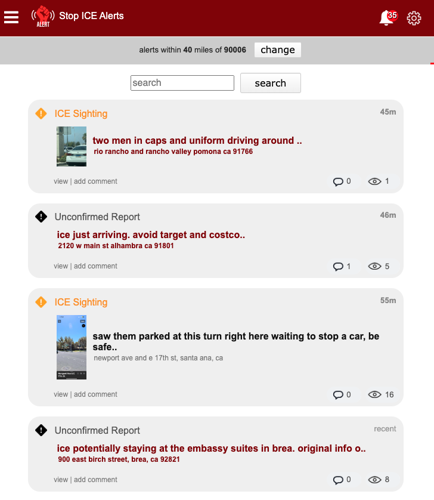

StopICE.NET

Founded by Long Beach resident, artist, coder and anarchist Sherman Austin, the website lets you make an account, search through zip codes and addresses and get updates on nearby reported raids.

People who also see ICE activity also have the option to report by texting REPORT to (877) 322-2299.

StopICE.NET has grown slowly and quietly over the years. It first gained traction in activist communities and local neighborhood watch groups, but its user base expanded significantly during past immigration crackdowns under the Trump administration. What was once a small tool primarily passed around in encrypted group chats and at organizing meetings has become part of a wider digital safety toolkit for immigrant communities.

The data on StopICE.NET is crowd-sourced but carefully reviewed. Submissions can include timestamps, license plate numbers and neighborhood information. If a submission is clearly misinformation or made in bad faith, it can be removed or flagged by moderators. As of now, the platform is primarily maintained by volunteers, with Sherman still involved in backend development.

For some users, StopICE.NET has also become a central hub where additional resources are shared—Know Your Rights guides, hotline numbers and even mental health contacts for those navigating trauma triggered by ICE presence in their neighborhoods.

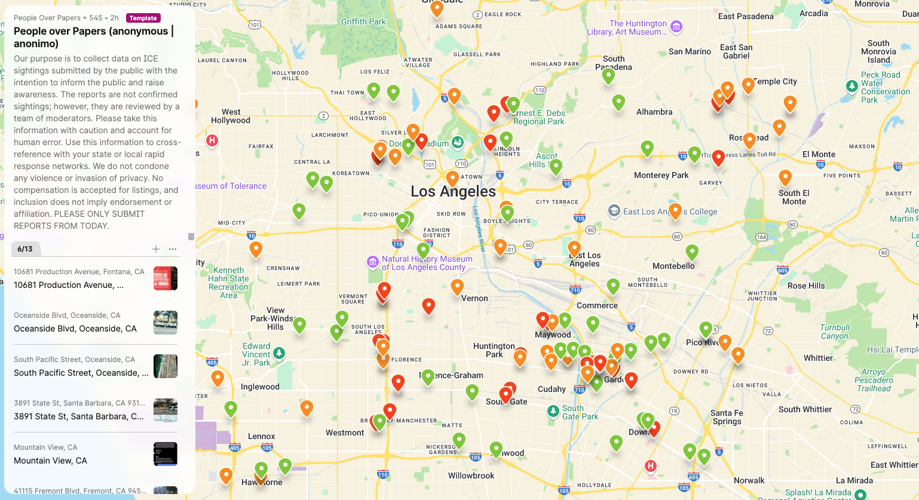

POP: People Over Papers (Padlet Map)

A platform created earlier this year by Celeste, whose last name we won’t share for their security and safety, has become one of the leading resources used by millions nationwide.

Currently, on the Padlet servers and platform, POP sources ICE sightings and encounters from tips and submissions, which are vetted by a team of volunteers across the country who take shifts every hour, around the clock.

Celeste and I often talk on Zoom in the midst of all of these raids, alerts, news and then some, she talks to me about the process of how, before the raids started in California, she planned two weeks off to catch up on life, then, POP was inundated with submissions.

The platform is simple. It's a nationwide map with pins categorized in colors detailing what is verified and what can’t be.

When you click on the pins, there are descriptors by the person who submitted. Some have photos of white vans, others are screenshots of social media photographs, while others are plain text.

“So if a hotline gets a call and then they have to drive out, they arrive 10 to15 minutes after the report already came in,” Celeste tells me. “The officers could have been gone. They could have actually been there, and they've left already. We have no idea what happened. So that's why it's important for people to document, record, take pictures, take notes, if you can, of everything that you're witnessing.”

The influx of activity on POP during this current wave of enforcement has challenged the limits of what small digital tools, many of which are operated entirely by volunteers, can handle on platforms like Padlet. Celeste tells me how difficult it has been to keep pace and how the accuracy of each report becomes more vital in an environment where misinformation spreads quickly.

During this time, immigrant families, mixed-status families and neighborhoods have lived in fear. The “Mexican Beverly Hills,” Downey, California’s downtown, is now considered a ghost town, because of both the reality of the raids and also because of the onslaught of possible raids being projected. There exists a muddy grey area still for immigrants, on whether to step out despite no notice of ICE sightings and whether a place where ICE visits will be visited again.

Celeste smiles when she tells me the impact of this platform. Some users report checking the POP map as part of their morning routine. Parents plan school drop-offs; delivery drivers decide their route; Teens text each other to confirm whether it’s safe to walk to practice. It has become, for many, more than just a platform—it’s a real-time lifeline.

Engineers needed

Padlet has crashed a few times this week. With millions of people using the service more than ever, Celeste tells me one of the biggest needs they have is for engineers and computer science developers who are open to sharing their services. The goal is to expand outside of Padlet soon and develop a stronger and accessible platform.

Celeste mentions that Padlet’s limitations are starting to show. While user-friendly and easy to set up, the map was never intended to host millions of clicks and real-time pins from across the nation. And as more people use it as a safety tool, the urgency to stabilize and scale grows by the hour.

At the moment, the map takes some skill to navigate, but it’s still one of the most robust forms of seeing the latest sightings and verified reports all along a map for people who possibly need to travel or have loved ones in different regions.

To date, there are hundreds of pins just in Southern California, with clusters appearing near freeways, known day laborer pickup sites, apartment complexes and even shopping centers. The patterns, while still anecdotal and some verifiable, are beginning to paint a picture of how ICE moves and where they focus.

As news grows of more surveillance, extended enforcement schedules and more projected protests, I asked Celeste what immigrants can do to further prepare.

“I would say try to build community. I think that's the most important piece, whether it be through protest groups, whether it be through book clubs. You know, I think community right now is super important,” she said.

This emphasis on community echoes across many immigrant-led and immigrant-serving organizations. In the absence of clear government communication, even by Democrats in California or real-time media coverage of enforcement activity, digital solidarity is becoming the new infrastructure. Whether through mutual aid groups that offer grocery pick-ups, alert channels, or simply group chats that send out real-time sightings, the ability to connect is, in many cases, the only thing standing between a routine day and detention.

In neighborhoods where these tools are shared widely, residents describe feeling slightly more in control, able to make decisions with the best information available to them. But even with these platforms, the stress remains. No app or map can erase the looming uncertainty many families live with daily.

Still, for now, many refresh the page, scour through Instagram stories and navigate multiple group chats. They wait for alerts. And they report when they can, knowing someone else might be doing the same for them.

(0) comments

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

Keep it Clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexually-oriented language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't Threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be Truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be Nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be Proactive. Use the 'Report' link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with Us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.