The Inland Empire (IE) is quietly cultivating one of the most dynamic literary ecosystems in California. At the heart of that effort stands the Inlandia Institute, a nonprofit organization based in Riverside, committed to publishing and celebrating the voices of local writers, especially those whose stories are left behind by traditional publishing gatekeepers.

Founded in partnership with the City of Riverside and Heyday Books, Inlandia began with a bold idea: that stories from the IE matter, and they deserve to be told on their own terms. The organization’s name was coined by none other than Juan Felipe Herrera, California’s first Latino Poet Laureate.

More than a literary nonprofit, Inlandia is a cultural movement, one that positions storytelling as a tool for healing, empowerment and visibility.

Executive Director Cati Porter describes Inlandia’s mission simply but powerfully: “To celebrate the region, to lift up the stories that are here, because people don't know we're here. We know we're here, we know what's going on, but we want everybody else to know.”

Inlandia does this through writing workshops, author events and book publishing—but most critically, through community partnerships that connect words to lived experience. From memoirs to poetry collections, children’s books to cultural essays, Inlandia offers platforms that reach across disciplines and identities, all rooted in the local.

At Inlandia, representation is integrated into every aspect. Minerva Canto, the president of the board of directors, states that Latinos participate "at every stage.”

“It’s a very participatory organization,” she explained. “We have community committees that are set up for the major aspects of Inlandia—which is publications and programming […] so we have a seat at the table. And that's important, obviously, in a community that is majority Latino.”

Canto points to the “Celebrating Cultura” series, created by former board president Frances J. Vasquez, as one example of Inlandia’s intentional programming. From Día de la Raza events or Cinco de Mayo celebrations, these community gatherings are part of what Inlandia is.

A prize with purpose

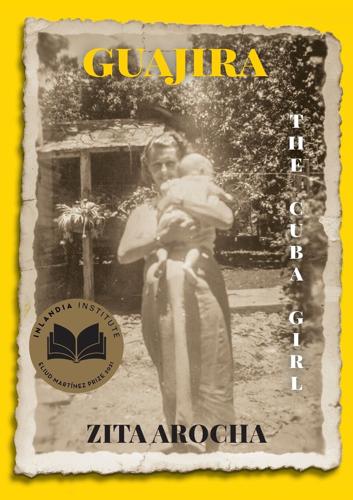

One of Inlandia’s projects is the Eliud Martínez Prize, a publishing award created to honor the late UCR professor and longtime Inlandia supporter. The prize offers $1,000 and a book deal to a writer who identifies as Hispanic, Latino/a/x or Chicana/o/x—and is intentionally inclusive in its eligibility criteria.

“This was an effort that was spearheaded by poet Liz Gonzalez, who is from San Bernardino,” said Canto. “She and I worked together to create the guidelines... Some people identify as Hispanic. Some people identify as Chicanos. So that was a whole major conversation.”

Canto also emphasized the importance of keeping the prize accessible to undocumented writers. She acknowledged the work of “undocuPOETS,” a group that has brought attention to how the guidelines of many major literary prizes often exclude undocumented immigrants—“writers who are constantly producing important works,” she explained. “I made sure that the guidelines were written so that we weren't exclusionary, but rather more inclusive.”

The first winner was journalist and author Zita Arocha, whose memoirGuajira, the Cuba Girl adds a new layer to Inlandia’s growing catalogue of works by immigrant voices.

Submissions open annually on November 1 and close on January 31.

Writing that transforms

Inlandia’s commitment to the region’s community is illustrated in the story of Lydia F. Theon Ware i, a once-homeless writer diagnosed with schizophrenia who now leads writing workshops for others navigating housing insecurity and mental illness.

Porter recalls the first time she reconnected with Ware: “She was approaching Inlandia about a workshop she had created called “Cartless, or Why I Didn't Get a Cart”, and this is when I learned her story.”

Ware had pitched her program to several shelters without success—until she came to Inlandia.

“She really needed someone, an organizational sponsor,” Porter said. “I said yes. And she's now been doing it for, I want to say, at least five years, maybe longer. She’s helped so many people, and they feel really good about themselves. They leave the program having written and created.”

This kind of work reframes who gets to be a writer and what kind of stories are considered worthy of support.

Inlandia’s first book, “Dos Chiles -Two Chiles”, by author and school teacher Julianna Maya Cruz, set the tone for what would come.

Cruz designed a class project aimed at connecting students with their family histories. Food was one perfect gateway. She asked her students to interview elders about a meaningful recipe, a prompt that she also took on herself. Turning to her grandfather, Julian, she documented his New Mexico green chili recipe.

As they cooked together, she recorded not just ingredients and steps, but the stories that unfolded—memories tied to place, family, and tradition. Although she was an adult when she wrote the story, Julianna chose to narrate it from the perspective of a child. The book includes family photographs and the original recipe, serving as both a personal archive and a reflection of how cultural identity can be preserved through everyday rituals.

Upcoming publications continue this tradition. “René Solivan’s Search Party” explores the chaos of a reluctant mother navigating family bonds, while “Tomás Hulick Baiz’s Mexican Teeth” blends magical realism and racial tension in a series of short stories.

Inlandia is not slowing down. This summer, they’re offering “Sundays with Sabraé,” at the Riverside Museum, a family storytelling event and “scavenger quest” to explore the museum led by anime artistSabraé Harris (aka Starlite Crystal). The six-part series will have its next session on June 29 at 1 p.m.

A table with no limit

As federal funding cuts loom, there’s also uncertainty.

“I fear that we haven't quite seen the effects,” said Canto. But they are preparing “trying to focus on finding additional sources of revenue […] we do have a lot of community support, and that comes in the form of not just dollars, but in terms of volunteers, and we do rely heavily on volunteers to help us run Inlandia.”

For both Canto and Porter, Inlandia is a unique project. Canto’s own journey began with a transformative memoir-writing workshop.

“I think it was [there] where I got to witness firsthand the power of Inlandia through a writing workshop and the community that it creates, and the empowering feeling of being able to tell your story because of the tools that I learned at this workshop,” she said.

For Porter, it’s a community of kin.

“I consider everyone in Inlandia a friend,” she said. “It is about supporting community. It is about lifting up stories of the people in this community, giving them a platform… Everybody should have a seat at the table. And you know, the table is very big, we all need to have a seat at the table. There's no limit to the number of seats we can have at the table.”

In a publishing world that too often builds walls, Inlandia is building bridges. And in doing so, it’s giving Inland Empire writers—and readers—a place to belong.

People interested in supporting Inlandia’s work by volunteering can contact Cati Porter at: cati.porter@inlandiainstitute.org.

(0) comments

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

Keep it Clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexually-oriented language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't Threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be Truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be Nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be Proactive. Use the 'Report' link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with Us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.