My late Mexican father, Salomón Huerta Chávez, Sr., never said, “I love you” to me. That goes for my seven siblings, except (possibly) for the youngest, Ismael. My father’s favorite. Whenever I teach and mentor graduate students at Harvard, I always advise them to ask “how” or “why” questions when they write academic papers. Hence, instead of judging my father or being hurt by his neglect (not the case), I ask, “Why was my father incapable of saying the three magic words—’I love you’—to his children and wife?” Without getting all Freudian, I’ve learned that it goes back to his turbulent and harsh upbringing in a small Mexican rancho in the beautiful state of Michoacán: Zajo Grande. At the rancho, along with his parents and ten siblings, he experienced poverty, violence and death.

Poverty and violence, accompanied by abuse, followed him to el norte. First as a bracero (guestworker/farmworker) and then as a resident of East Los Angeles’ notorious Ramona Gardens public housing project or Big Hazard projects—named after the dominant gang. While there are aspects or contradictions of my father that I’ll never discuss publicly or privately, as I reflect on some of his harsh experiences and impactful interactions with me in these vignettes (and elsewhere), I’ll always appreciate the mental fortitude that inherited from him, allowing me to survive/thrive against tremendous obstacles (poverty, violence, racism) as a Chicano in white America.

El Robo

When my late Mexican mother, Carmen Huerta Mejía, was only 13 years old, she was almost abducted. The brute’s name was Hilario. La queria robar. It took place in front of her home in the rancho. If she was successfully abducted for one night or more, to save her reputation and the family honor, regardless of what occurred during the abduction, she would have no choice but to marry him. Fortunately, my mother escaped from the brute’s grip, hitting him on his forehead with a rock. Wanting to kill her, the bloodied and she blinded Hilario shot at her with his revolver, missing her as ran back home. (Many moons later, whenever I asked my mother to tell this horrific story, instead of being traumatized, she told it with a smile, as if it were a dramatic scene in an American Western film.)

Since my father also liked my mother at the time, once he learned of Hilario’s botched plan, which included paying a relative to take him away for the day, my father sought revenge without success. My father was 21 years old. Most of the men in the rancho, including my father, were armed with weapons to defend their families, lands and crops. Hilario was lucky to have escaped. After my father courted my mother, they wed two years later. At 16 years old, given the customs of the rancho at the time, my mother gave birth to my eldest sister, Catalina.

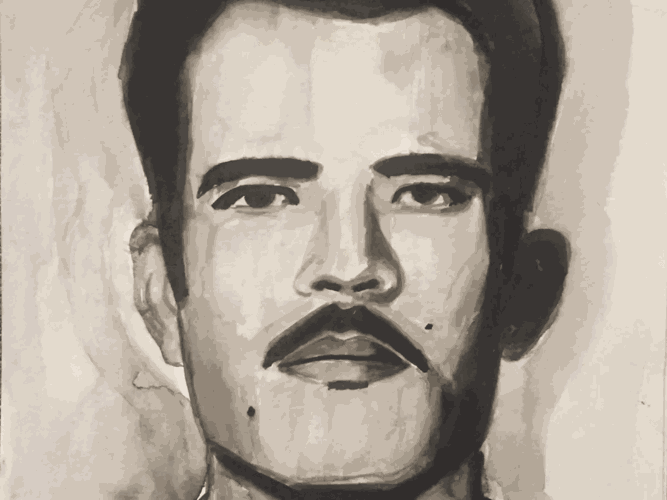

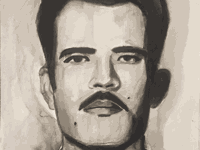

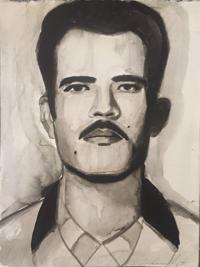

Salomón Huerta Chávez and Carmen Huerta Mejia (circa 1955) Morelia, Michoacán, México

Family Feud

During the mid-1900s, the Huertas were engaged in a family feud with another family in Zajo Grande, like in the case of America’s famous feud between the Hatfields and McCoys in Appalachia. As my father—the eldest male—immersed himself in this feud, he engaged in gunfire with his enemies. He was shot several times. Tragically, in 1958, my tío Pascual was killed by the rival family. He was only 20 years old. Like my father and uncles, he was family-oriented, courageous and handsome. Avenging his brother’s murder, my tío Javier became one of the fiercest defenders of the familia.

Tired of the violence and fearful of losing more sons to this senseless feud, in the 1960s, my abuelo Martín, as the patriarch, relocated most of his familia to Morelia, Michoacán, and Tijuana, Baja California.

The Bracero

Like millions of rural Mexicans, my father participated in the Bracero Program (officially the Mexican Farm Labor Program). This binational, guestworker program between the U.S. and Mexico occurred from 1942 to 1964. An estimated 4.6 million Mexicans participated in this program to meet America’s labor shortage in our agricultural fields. Apart from being exploited for his labor power, during the inspection process, he was forced to strip naked in front of his paisanos. I will never forgive white America for humiliating my father and his paisanos.

Moreover, he was also sprayed with DDT. DDT causes cancer and other health ailments. My father died at 66 years old of prostate cancer. Causation?

The Projects

While our immediate familia lived in Tijuana and Hollywood, California, with our extended familia, in the early 1970s, we moved into notorious public housing projects in East Los Angeles (Boyle Heights). As Mexican immigrants, my parents were not privy to the many problems that plagued the Big Hazard projects. This included poverty, violence, gang activity, drugs, state violence (cops) and state surveillance. Essentially, it was one of the most dangerous neighborhoods in the country.

For protection in the projects, my father never left home without .38 Special revolver. In our apartment unit, he placed it either inside his green suitcase or on top of his nightstand. As an acclaimed artist, my older brother, Salomón, Jr., occasionally utilizes our father’s gun as a subject for his artwork. He uses it to reflect on his childhood memories when he would bring him food, pan dulce, fruits and drinks to his nightstand. His aim is not to glorify or romanticize guns or violence. Instead, he seeks to tell his story or relationship with our stoic father via art.

“Gun with pan dulce,” oil on canvas, Salomón Huerta (2018)

The Homies

When many fathers give their kids a soccer ball or basketball to practice or play at the park, when I was 12 years old, my father handed me his gun. The reason? One of the local gang members (homeboys) wanted to jump him (physically assault him) since he allegedly hit his younger brother. One cold night, the homeboy and his homies waited for him outside of our apartment unit. Instead of hiding or calling the cops, my father decided to approach the homeboy and explain the misunderstanding. Man to man. In preparation, he instructed me to put his gun under my belt in my backside. Unbeknownst to me, I was his back-up. Suddenly, without any further instructions, I followed my father outside. First time that I saw him nervous. He then walked towards the homeboy and his homies. After a few tense minutes, they shook hands. My father returns in my direction, telling me, “Vamos a casa.” We watched a Western television show. I was bewildered at how calm he was, as if our lives weren’t at risk a few moments earlier.

“Untitled,” shadows of homeboys, Salomón Huerta (circa 1992)

Malibu

As a teenager, I abhorred manual labor. While gifted in mathematics, I didn’t spend too much time doing homework, either. Up to the 10th grade, I spent a lot of my free time watching my favorite television programs. Worried about my laziness, my mother forced my father to take my older brother and I to work as day laborers in Malibu, California. While my brother was 15 years old, I was 13. One summer morning, my father woke us up at 5:00 a.m. After getting ready for the unknown, we took two buses from the Eastside to the Westside. It took us two hours to get to an empty parking lot. Suddenly, Mexican men began to populate the lot, patiently waiting for rich white people to pick them up for work in their luxury cars (BMW, Mercedes, etc.). While I initially didn’t understand what was happening, once I saw my father ran towards a car and wave at me to follow, I realized that hard labor that awaited us.

Once we arrived at the mansion with the large backyard—adjacent to the beautiful ocean—I dreaded the entire day. After working for a couple of hours pulling weeds, I kept asking my father when the nightmare would end. Quince minutos más. Once my father told me to stop, I erroneously thought it was time to go home. Lunch time. While eating my lunch (a carne asada burrito) and thinking about the next four hours of hard labor, I cried in silence. I then made a promise to myself: “I’m too lazy for manual labor. I’m going to college.”

Four years later, I’m enrolled at UCLA as a math major. After taking a hiatus for several years from my studies to become a community organizer, I returned to university and earned a B.A. (History) and an M.A. (Urban Planning) from UCLA. I also earned a Ph.D. (City and Regional Planning) from UC Berkeley. Apart from my tenured faculty position, I now teach and mentor graduate students at the Harvard Divinity School.

While I have more to accomplish in my life as a proud son of Mexican immigrants, on this Father’s Day, I say to my apá the two magic words that his upbringing inhibited him telling me: “Te amo.”

(0) comments

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

Keep it Clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexually-oriented language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't Threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be Truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be Nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be Proactive. Use the 'Report' link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with Us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.