LACMA’s newly acquired artworks, “Creole Woman from the City of Guadalajara” and “Creole Man from Mexico City” (c. 1710), by Manuel de Arellano. (Photo courtesy of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art)

Last month, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) hosted its 39th annual Collectors Committee fundraiser, a weekend for donors to gather for art, food and wine, and for Committee members to vote on which artworks will join the museum’s permanent collection. This year, together with acquisitions by Virginia Vezzi, Hiroshi Sugimoto, Max Beckmann, Chiura Obata, Tokio Ueyama and Miné Okubo, LACMA acquired two pieces by Manuel de Arellano.

Arellano’s “Creole Woman from the City of Guadalajara” and “Creole Man from Mexico City” (c. 1710), which are only two of the Mexican artist’s many groundbreaking precursors to the famous casta (caste) paintings, were acquired by Ilona Katzew, the museum’s curator and department head of Latin American art.

As the first Latin American art curator at LACMA since 2000, she has built the Latin American collection from scratch with artworks by casta painters such as Miguel Cabrera, Juan Patricio Morlete Ruiz and Vicente Albán. When she went on a hunt for new additions a year ago, Katzew couldn’t believe it when she spotted casta paintings by Arellano at an auction in Vienna. After first being bought by a dealer in Spain and squaring away the legal paperwork that comes with acquiring older art, it took a year before LACMA officially had them.

“I'm happy that the [Collectors Committee] decided to acquire them because they're major additions, not just to the collection, but in terms of what they reveal about Mexican painting, the development of casta painting, what they say about the construction of race in the early modern world and how dress is used to construct identity,” Katzew said. “The meaning was used at that time and it's still used in our time. I think those examples are brilliant in that regard.”

Casta paintings stem from the term “casta,”meaning “lineage” in Spanish and Portuguese, and in colonial Mexico, it was used to describe the hierarchical, race-based caste system. According to writer Sindy Valdez, the casta system “categorized individuals based on their racial makeup, influencing their social status, rights and opportunities.” The categories within this system include Peninsulares, Españoles (Spaniards), Criollos (Creoles), Mestizos, Mulatos, Zambos, Castizos, Moriscos and Tresalvos.

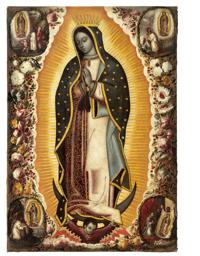

Manuel de Arellano and Antonio de Arellano “Virgin of Guadalupe (Virgen de Guadalupe)” (c. 1691), oil on canvas. (Photo courtesy of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art)

Before the 18th century, art in Mexico was typically centered around religion and portraits, but this shifted when casta paintings emerged. These artworks provided a window into the Mexican caste system by depicting multiracial families wearing colorful and distinguished attire. Made accessible to a broader audience, not only the elite, in churches and other public areas, most casta paintings have 16 separate canvases and offer insight into the significance of race and class in colonial Mexico.

“They look like harmonious images of racial diversity, except for the paintings that show scenes of violence or more virulent scenes,” Katzew said. “They're very paradoxical that way. It's that tension between what they show and what they say through the inscriptions that puzzles people of our time. They tell a lot about colonial history, about the history of painters and painting and about daily life in Mexico. It's the perfect trifecta in terms of the information that they provide.”

Arellano is one of the artists who had a major hand in making casta paintings so pivotal and groundbreaking, making LACMA’s acquisition of two early prototypes of his casta paintings a remarkable find. Born in 1662 to a dynasty of artists in Mexico City, Arellano trained with his father, Antonio de Arellano, and began creating experimental paintings in 1690. Following the mistreatment of the Indigenous and mixed-race working class, the consideration of Spaniards as second-class citizens and the poor perception of the Americas, Arellano constructed “a view of a mixed yet orderly and prosperous society,” according to Katzew.

The artist accomplished this through pieces like “Creole Woman from the City of Guadalajara” and “Creole Man from Mexico City” (c. 1710). In these works, the man wears a modern three-piece suit and Spanish cape, alongside a sword, which displays his high social standing, and the woman wears a combination of local and European clothing.

“[Arellano’s work] painted a pathway for the development of casta painting throughout the rest of the 18th century,” Katzew said. “Those paintings span over 100 years with over 100 sets. The chance to have them here at LACMA to tell a more inclusive story of the development of Spanish American art is expansive and amazing.”

These new artworks are finding a home next to Arellano’s “Virgin of Guadalupe” (c. 1691), which LACMA acquired in 2018. A significant image in the Catholic church, many artists have copied the image of Mary in their own ways, and Arellano and his father are not the first ones to do so. What sets theirs apart is the added inscription “touched to the original,” or “tocada a la original,” and the Virgin surrounded by four vignettes. Katzew always knew that she wanted to add an image of the Virgin to the Latin American Art collection, but held off for a version directly copied from the original, which was created by Juan Diego in 1531.

“When the image by Antonio and Manuel de Arellano came up, it was beautiful,” Katzew said. “I added it to the collection a few years ago. She's one of the most popular images in the collection.”

Arellano’s artwork and contribution to casta paintings have immensely impacted not only the world’s view of the Americas but also influenced a genre that has created nearly 2,000 works of art. These works became better studied in the 1980s and 90s and have recently elicited major interest in casta paintings, regardless of differing opinions and questions of their meaning.

“They're very much paintings of their own times, which is why people are so fascinated by them,” Katzew said. “The impact is huge nowadays because they allow us to see how race and racial ideologies were thought about in the early modern period, and how Mexico gave a unique visual form to this way of creating social hierarchies and pointed to a sense of abundance of the land. They're not black and white, they're in between. That complexity shows us we can look at things from different angles.”

These complexities of casta paintings can be further discussed and considered in April 2026, when Arellano’s new additions will be on view at LACMA’s incoming David Geffen Galleries.

“It's going to be really nice to share this with everyone and get people to engage with the material,” Katzew said. “That's where I get the most satisfaction.”

(0) comments

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

Keep it Clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexually-oriented language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't Threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be Truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be Nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be Proactive. Use the 'Report' link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with Us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.