Rather than framing Violeta Parra’s artistic journey as a linear ascent, the biography captures its recursive rhythms, contradictions, and the emotional cost of defying expectation.

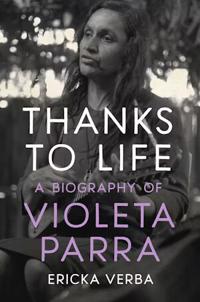

Rather than offering a static portrait of Violeta Parra, Ericka Verba’s “Thanks to Life”presents a kinetic study of an artist who continually remade herself in response to the pressures of nation and global politics.

While biographies can often solidify their subjects into monuments, Verba resists this temptation, presenting Parra instead as a figure in ceaseless negotiation with the forces that sought to define her. Drawing on extensive archival research and personal immersion in the musical traditions Parra herself helped ignite, Verba constructs a layered narrative that acknowledges the inevitable contradictions of any life lived so defiantly.

Verba writes, “At age fifteen, Violeta may not have known where she was going, but she knew where she came from.”

Yet, even as Verba attends to these nuances, her critical distance sometimes falters, risking a tone of reverence that softens the harsher edges of Parra’s ambitions and failures.

By threading the concept of the “invented self” throughout the biography, Verba invites the reader into a conversation about the identity construction, particularly what gender studies scholar Judith Butler’s calls the articulation of performativity. In Verba’s account, Parra’s embrace and manipulation of her Indigenous identity within European contexts illustrates not merely survival but active subversion. While the book captures the external pressures shaping Parra’s image, it sometimes stops short of fully interrogating the ethical ambiguities that accompany such self-fashioning. The shifting claims of ancestry and the strategic use of marginalization, so vividly recounted, beg for deeper engagement with the postcolonial critiques of authenticity and commodification.

The emotional force of Verba’s prose often comes from her vivid reconstruction of Parra’s environments, whether the towns of Chile or the cold, exoticizing salons of Geneva. Here, the narrative’s aesthetic attention recalls the idea of the chronotope, where time and space are thickly intertwined to define the social world of the character. In Verba’s hands, these settings do not simply house Parra; they work upon her, producing new modes of expression that both draw from and resist the ideological weight of place. Still, despite this structural sensitivity, the biography occasionally leans on a linear progress narrative that flattens the recursive and often regressive rhythms of Parra’s personal and artistic development.

Violeta Parra’s life, as portrayed by Verba, unfolds as a series of bold reinventions shaped by exile, ambition and the pressures of global politics.

One of the subtle yet persistent undercurrents in Verba’s narrative is the way exile, both voluntary and involuntary, shaped Parra’s creative possibilities. Her repeated crossings between Chile and Europe are never framed as glamorous adventures, but as exhausting, sometimes alienating movements through different zones of political and cultural expectation. Verba keeps this tension alive without resolving it too neatly is a testament to her careful handling of historical material.

Equally compelling is Verba’s attention to Parra’s visual art, which receives serious consideration rather than being treated as a mere supplement to her musical legacy. The book’s discussions of Parra’s arpilleras, paintings and sculptures recognize these works as central expressions of her political and personal world, not side projects. In one passage, Verba describes the reception of Parra’s visual work in Geneva and Paris, noting the simultaneous exoticization and genuine admiration she received. This attention restores a crucial dimension to Parra’s artistic career, allowing readers to see her not merely as a singer of protest songs but as a full-spectrum creator, capable of reimagining Chilean folklore through multiple artistic vocabularies.

Verba is also attentive to the politics of gender that structured Parra’s career, although she is careful not to turn the biography into a simple indictment of sexism. Instead, she shows how Parra’s struggles for artistic recognition often intersected with, but were not reducible to, the broader systemic exclusions faced by women in Latin American cultural spheres. This attention to nuance is particularly evident in Verba’s treatment of Parra’s relationship with male collaborators and patrons. Rather than framing these relationships solely as exploitative or supportive, Verba leaves space for their contradictions, recognizing how Parra navigated and sometimes manipulated these dynamics to further her own artistic ambitions.

Throughout “Thanks to Life,” Verba threads a quiet but persistent meditation on the theme of reinvention. Parra’s movement from popular performer to folklorist to visual artist is not portrayed as a linear evolution toward self-actualization but as a series of strategic, sometimes painful redefinitions driven by shifting personal needs and political imperatives. The biography does not romanticize these transitions; it acknowledges that they often came at great personal cost and were fraught with disappointment. Yet in Verba’s telling, they also reveal Parra’s refusal to be fixed by the expectations of others — a refusal that, in the end, is one of her most enduring legacies.

If “Thanks to Life” leaves any unanswered questions, it is because Verba wisely recognizes that no single biography can fully contain a figure like Violeta Parra. There is a humility in the book’s structure, an acknowledgment that Parra’s life spills over the borders of any one narrative frame. Rather than attempting to close that gap, Verba invites readers to dwell in it, to listen more carefully to the silences, ruptures and self-inventions that animated Parra’s work.

When considering Parra’s politicization, Verba deftly portrays her songs as acts of witnessing rather than didactic preaching, positioning her as a precursor to testimonial traditions in Latin American literature. Yet what remains less developed is the structural tension between Parra’s avowed populism and her eventual entanglement with elite cultural institutions like the Louvre. Pierre Bourdieu’s theories of cultural capital hover unspoken behind these developments, suggesting a richer, more ironic reading of Parra’s late career as one caught between insurgent authenticity and the seductions of prestige.

As portrayed in the book, “These early commentaries on Parra’s guitar instrumentals could serve as a template for how her creative work would be received over the remainder of her life, be they her modern compositions or her embroidered tapestries hanging in the Louvre Palace.”

Verba, through all of this does achieve something rare in biography: it portrays its subject as a maker not only of art but of myth, without wholly surrendering to that myth. Verba’s profound admiration for Parra occasionally lapses into a protective impulse, buffering the artist from the full critical weight her life invites. Even so, the book’s refusal to settle for an uncomplicated narrative honors the spirit of its subject, who moved through the world not as an icon in waiting but as a restless, volatile force. In refusing to perfect Parra, Verba gestures toward a deeper truth: that to be truly radical is to remain unfinished.

You can buy a copy of “Thanks to Life: A Biography of Violeta Parra" here.

(0) comments

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

Keep it Clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexually-oriented language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't Threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be Truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be Nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be Proactive. Use the 'Report' link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with Us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.