This story was originally published by EdSource. Sign up for their daily newsletter.

Top Takeaways

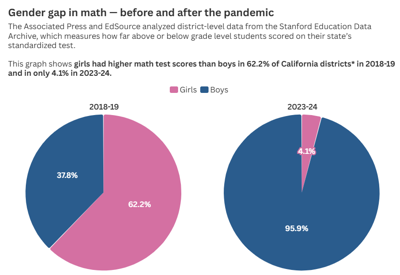

- Girls had higher math scores in 62% of California districts in 2018-19, but only 4% in 2023-24.

- Boys outscored girls in math in nearly 9 out of 10 districts nationwide, a dramatic reversal of pre-pandemic trends.

- National experts have not definitively pinpointed which factors contributed to this widening gap, but school closures at the height of the pandemic do not seem to explain it.

Just before the pandemic struck, girls had overtaken boys’ scores in math and finally closed the long-standing gender gap in a subject that is a gateway to the fields of science, technology, engineering and math.

Math scores dipped across the board in the wake of the pandemic, but girls’ scores dropped far more precipitously and have continued to remain lower than boys’.

The Associated Press analyzed data from the Stanford Education Data Archive and found that in the decade before the pandemic, girls had not only improved math scores nationwide, but they were also outscoring boys. But then by 2023-24, boys on average outscored girls in math in nearly 9 out of 10 districts.

The data, which looked at scores across 15 years in over 5,000 school districts, was based on average test scores for third through eighth graders in 33 states.

National experts in math have not definitively pinpointed which factors have contributed to this widening gap, but school closures at the height of the pandemic do not seem to explain it, according to Megan Kuhfeld, director of growth modeling and data analytics for the education research company NWEA.

“It wasn’t something like COVID happened and girls just fell apart,” Kuhfeld said.

A separate study by NWEA found gaps between boys and girls in science and math on national assessments went from being practically nonexistent in 2019 to favoring boys around 2022.

This national trend holds true in California as well. Girls had higher math scores in 62% of California districts in 2018-19, but only 4% in 2023-24, according to the Stanford Education Data Archive.

The widening gender gap from 2018-19 to 2023-24 is also apparent at districts throughout the state:

- Lake Tahoe Unified School District had one of the largest relative drop-offs between girls’ and boys’ math scores, with girls’ scores falling 33% of a grade level and boys’ scores rising 82% of a grade level.

- In the Los Angeles Unified School District, girls’ math scores dropped the equivalent of 13% of a grade level, while boys improved around 29% of a grade level.

- Greenfield Union Elementary School District had one of the largest relative drop-offs between girls’ and boys’ math scores, with girls’ scores falling 75% of a grade level and boys’ scores rising 10% of a grade level.

- It wasn’t all bad news: El Segundo Unified School District saw some of the biggest improvements for girls in math, with girls’ scores rising 67% of a grade level. That was less than the 87% of a grade level improvement in boys’ scores.

Studies have indicated that girls reported higher levels of anxiety and depression during the pandemic, plus more caretaking burdens than boys.

At the Fall River Joint Unified School District in Shasta County, Superintendent Morgan Nugent sees student mental health as the greatest issue leading to the widening gender gap in math scores. He said he saw students’ mental health diminishing through the pandemic — most strongly among girls — and ultimately impacting their education, from their attendance to their test scores.

“Unless we address mental health issues, then everything we found that was very successful in the past isn’t going to work,” said Nugent.

However, the dip in academic performance did not appear outside STEM. Girls outperformed boys in reading in nearly every district nationwide before the pandemic and continued to do so afterward.

In the years leading up to the pandemic, schools were increasingly deemphasizing the role of drills, repetition and rote memorization in math, according to Kristine Ho, director of the statewide UCLA Mathematics Project. Math became more conceptual, with teachers emphasizing that there could be many ways to count or solve a problem.

After returning from remote learning, teachers felt incredible pressure to get students back on track, and many felt like they didn’t have time to have open-ended conversations.

“There was this sense of fear: How are we going to make up for what we missed?” Ho said.

But she says that a more inclusive style of teaching seemed to be paying dividends for other marginalized student groups, such as Black, Latino and students with disabilities. These groups also lost ground on math and have been slower to recover.

“Maybe what girls needed was that inclusive, open space where they can have the ability to say what they think,” Ho said.

Michelle Stie, a vice president at the National Math and Science Initiative, agrees, saying that old practices and biases likely reemerged during the pandemic.

“Let’s just call it what it is,” Stie said. “When society is disrupted, you fall back into bad patterns.”

There are other theories that have been floated to try to explain why girls lost so much ground during the pandemic. One is that girls still face negative gender stereotypes about their abilities in STEM fields. There is also a concern that an increase in behavior problems among boys means that boys have been getting more attention from teachers.

“We don’t have hard evidence for any of these theories,” Kuhfeld said.

However, there is research showing that girls’ enrollment in eighth grade algebra dropped in California. The share of boys who remained enrolled in eight grade algebra between 2019 and 2024 remained steady at 24%, while girls’ enrollment dropped by 2 percentage points to 25%, according to research from NWEA.

In the Palo Alto Unified School District, girls have actually slightly gained more ground than boys since the beginning of the pandemic. Scores among both genders gained about a quarter of a grade level between 2018-19 and 2023-24. Just before the pandemic, the district rolled out a new requirement that all eighth grade students take algebra. That means district students are a year ahead of most California students.

Higher math standards require the school to ensure that students are on track from an early age and intervene with struggling students, particularly as they transition from elementary to middle school, and then middle school to high school, according to Associate Superintendent of Educational Services Guillermo Lopez.

Palo Alto isn’t like other communities. There is a high demand for rigorous math and STEM preparation in the Silicon Valley district, where many parents work in the tech industry. But Lopez says that the district works hard to keep all students on track — especially those who have moved in from neighboring districts with different math expectations.

There isn’t much data to explain why the gender gap reopened, and math experts worry that we won’t know. The Trump administration has slashed education research programs. Ho notes that federal funds for professional development have also dried up, which will make it harder to address any achievement gaps.

Nugent also foresees new challenges due to losing federal funding.

Fall River Joint Unified recently lost about $80,000 in funding after the federal administration cut into the Secure Rural Schools program. While it is a smaller amount than what some of their surrounding districts are losing, Nugent said it’s a significant amount for a small, rural district to lose.

Soon after the cuts were announced, a teacher left the less than 2,000-student district and the students in that classroom needed to be redistributed to other teachers. The sudden increase in class size could impact teachers’ ability to offer students focused attention in any subject, including math. The teacher who left was at an elementary school in the district, which Nugent said means the district may not see the impact of this change until several years from now.

“Unfortunately, these things here erode our ability to set a kid on a right path and have those mathematics frameworks anchored in and ready to go,” he said.

The Associated Press contributed to this report. Read the AP’s national story here.

(0) comments

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

Keep it Clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexually-oriented language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't Threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be Truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be Nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be Proactive. Use the 'Report' link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with Us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.