The before and after of the Section 14 fires that displaced hundreds of Black and Latino domestic workers.

Pearl Devers was just 12 years old when she stepped outside her family's home in Palm Springs and noticed wisps of smoke forming in the distance. The smell permeated the air but it was unclear where the fire was originating.

In the 1950s, Palm Springs was building its reputation among the rich and elite in Los Angeles as a refuge from the bustle of the city. Celebrities such as Frank Sinatra, Marilyn Monroe, and Elizabeth Taylor were known to frequent and host lavish weekend Hollywood getaways.

Devers lived with her parents and siblings in an area of Palm Springs known as Section 14. The one-mile square tract of land, located near downtown, was an ecosphere, a vibrant community of mostly working-class Black, Indigenous, and Latino residents.

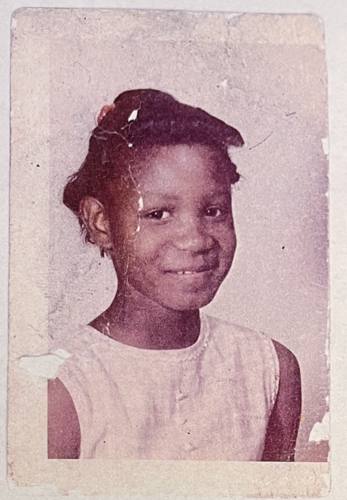

Childhood photo of Pearl Devers, then Pearl Taylor.

Many Black and Latino domestic workers moved to Section 14 after Agua Caliente tribal members leased the land out to the city. The local Indigenous community was provided with a source of income and many of the new residents were provided easier access to their employers. The residents filled a much-needed gap in the domestic workforce as the developing area increased in popularity.

It was a neighborhood established against the backdrop of discriminatory housing policies that were widespread across the United States at the time. “For me, it was home,” said Devers, now 73, who spent much of her childhood in Section 14. “The neighborhood was unified, we were very close-knit. It was like a village.”

When the mysterious fires began in the late 1950s, Devers's house, along with several others, were set ablaze. The circumstances would remain unclear to the displaced residents of Section 14 for years. Six decades on, survivors are seeking justice after discovering that their homes were burned down to make way for luxury tourism and commercial development.

Devers’s father, Robert Taylor, was a community leader. He helped found the first NAACP chapter in Section 14, which has since been disbanded. Taylor often hosted prominent civil rights leaders for dinner, including Thurgood Marshall and Jesse Jackson. Taylor was also a carpenter and built several homes in Section 14, including his own.

Her mother, Eula Taylor, was a stay-at-home caretaker who picked up housekeeping work for additional income. Lucille Ball was one of her more famous clients, along with the family of American aviation pioneer Amelia Earhart, Devers said.

Devers recalls playing outside with the neighborhood kids. She said it was not uncommon for Black families, like her own, to share food and resources with the Latino families in Section 14. “We knew each other closely and were the kind of community to share a cup of sugar with the neighbors,” she said.

It was not uncommon for residents of Section 14 to be active members of the local church.

Omar Valdez, a classmate of Devers’s from Frances Stevens Elementary School, shared similar memories of growing up in Section 14. Valdez recalls coming home to the smell of his aunt and grandmother cooking beans and making fresh tortillas.

Valdez’s childhood home was next to the church and his family was active members of the clergy. The church frequently hosted neighborhood fiestas. “It wasn't just for the Mexicans, it was for the entire neighborhood,” he told CALÓ News.

Children in Section 14 frequently played outside

Valdez’s mother, Rafaela Valdez, was a caretaker and writer. She published, both in English and Spanish, for The Desert Sun, the local newspaper. She also nannied for Mayor Frank Bogart, who later became a controversial figure for his alleged role in the fires that demolished Section 14.

“She basically raised his older children,” said Valdez. “We would see him around because he would drop my mother off after work sometimes. He had a very large personality.”

By the mid-1950s, Section 14 began attracting the interest of commercial developers as Palm Springs gained popularity. Residents felt the growing pressure from city officials to leave.

This pressure came to a breaking point between the late 1950s leading to the mid 1960s when residents of Section 14 would come home to discover their houses had caught fire. “There wasn’t one specific day this all happened,” Devers said. “This happened over a period of time.”

Subsequently, her mother and siblings moved in with a church friend who lived a couple of houses down. But they only stayed for a short time. Soon, that neighbor’s home also burned down.

Although Devers’s family relocated approximately six times, her father refused to leave the neighborhood. Her mother remembers him saying, “They're going to have to fight me to get in here or they're gonna have to burn me out,” according to Devers.

Taylor continued moving her children in with different church friends, continuously relocating as the homes they moved to also burned down. Eventually, Devers and her family left Section 14 altogether. “I literally watched the neighborhood disappear before my very eyes,” she said.

Valdez’s family, on the other hand, retreated to "the middle of the desert," where only one other family, also displaced by the fires, lived. Valdez said that he returned to the ruins of his old house once. It was gutted. “It was really spooky, it wasn't our house anymore” Valdez recalled.

Shortly thereafter, during a separate visit to their community church in Section 14, his family drove past their old neighborhood and saw that the city had bulldozed the area.

Section 14 was known for its prominent Latino and indigenous population.

Like Devers and Valdez, many victims of Section 14 lost their belongings and livelihoods. It was estimated that the displacement affected more than 1,000 residents and their descendants.

Devers's father never recovered from the emotional and financial loss. He succumbed to alcoholism after being unable to secure a loan to save his family’s house. Devers’s mother eventually filed for divorce. Taylor passed away at age 68.

Devers describes her father’s descent into addiction as “devastating,” especially as she had always considered him a hero in the community. “I used to play with his carpenter's belt and all the little tools,” she said, “I was very close to my father.”

For decades, the City of Palm Springs denied any wrongdoing or involvement in the fires. In 2020, amid the thick of the pandemic, several of the remaining survivors connected over Zoom calls with one another.

Around the same time, Palm Springs residents began to advocate for the removal of a statue of former mayor Bogert from City Hall. Many saw Bogert as responsible for the events that led to the demolition of Section 14 since he presided over the city during the time of the fires.

Invigorated by the momentum of the George Floyd movement, survivors of Section 14 began to organize for reparations. In September 2021, a formal apology was issued for the city's role in the forced eviction of families from Section 14.

Survivors of the Section 14 fires and advocates rally together for justice. (Areva Martin, the Los Angeles civil rights attorney representing plaintiffs is pictured on far left and Pearl Devers is pictured on the far right).

Valdez said reconnecting with other Section 14 families brought up a lot of feelings and allowed him and others to process their experiences collectively. “It just completely brought me back to Section 14,” he said, “I remembered everybody, I remembered how it was and I thought that's the way it should be.”\

The movement has also catalyzed a larger conversation around reparations. In 2022, survivors of Section 14 filed a lawsuit, demanding long overdue compensation for the loss of homes and personal property.

Areva Martin, a Los Angeles civil rights attorney representing the survivors and descendants of Section 14, spoke with CALÓ News about the ongoing lawsuit. According to Martin, residents of Section 14 were racially targeted by the city. However, instead of resorting to eminent domain, city officials exploited ties with the city's fire department to systematically burn and demolish their homes, as detailed in the historical documents uploaded to the city’s website. Advocates claim there is sufficient evidence in the documents showing that Palm Springs officials collaborated with a federal agency when the fire department burned homes in Section 14.

Martin emphasized that the primary aim of the lawsuits was to hold the city accountable for its actions and provide compensation for losses incurred by her clients.

In April, the city offered a $4.3 million settlement to 145 properties, but the initial offer was rejected. “We believe the losses are substantially higher than the approximate $5 million that the city has put on the table,” said Martin. She estimates the losses to exceed $2 billion dollars.

Martin says they are cautiously optimistic about continued negotiations and believe they can reach a fair resolution. They presented the city with a counteroffer and will continue to work in good faith until a settlement has been reached.

For many former residents of Section 14, the lawsuit represents just the first steps toward addressing the communal harm and trauma they’ve experienced. Many have expressed relief in being able to finally speak out about the events that led to their displacement.

Valdez acknowledged that there had been a notable lack of connection among the former residents of Section 14, with many failing to initially recognize the collective trauma they had experienced. However, the chance to come together and reunite has initiated a process of reconciliation and healing for some long-standing emotional wounds and grievances.

Although most survivors from the Section 14 fires are now in their 70s or older, they are inspired and motivated by the enthusiasm and passion of the younger generation of activists. Devers mentioned that being part of a community with others who also grew up in Section 14 helped them gain clarity about the injustice of their circumstances.

“We have a voice, and now that we know better, we can do better,” said Devers. “That’s what we're doing. We’re taking charge.”

(0) comments

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

Keep it Clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexually-oriented language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't Threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be Truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be Nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be Proactive. Use the 'Report' link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with Us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.