It has been a little more than a month since I had to say my goodbyes to my father, who left the United States for his hometown in Queretaro, Mexico. The last time I hugged him was on a late-November evening as he entered my cousin’s truck, the car that would take him to the Tijuana airport.

After 17 years, my dad decided it was time to go back to Mexico, reunite with his family and care for my grandmother, whose health has not been the best in the last couple of years. I have stayed behind to pursue my career in journalism. My mother is remarried and plans to someday go back to Mexico, too, at some point.

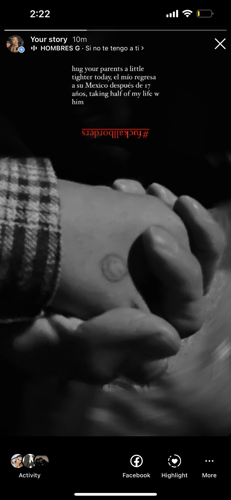

“God bless you mija, take care of yourself, and do not be eating too much salt,” he told me as he was getting ready to board the truck. I held his hand and told him not to worry about me. He gave me his blessing and told me that he loved me. What followed was the longest hug I have ever received in my life. As the black truck my father was in drove away, my heart felt like it had shattered into a million pieces.

I’m still trying to tape back the pieces of my very-much bruised heart. I have a feeling the repair of my heart will be a lifelong journey, or until I see him again. The last month or so has been the longest month of my life, or at least that’s what it has felt like. There are days when I can feel content and excited to hear his voice over the phone, almost forgetting that he is hundreds of miles away. But there are other days when I miss him so much that’s the only thing I can think of, making it hard to get out of bed and go on about my day.

Trying to stay afloat and keep a good attitude has been harder with the holidays. The end of each year has always been bittersweet for me. This was the first, in 17 years, that I have spent away from my father. Every Christmas and New Year, my father and I would step away from the loud, family celebration to call my grandparents, aunts, and uncles back in Mexico. In those calls, which would last approximately 20 minutes, we would wish them well and tell them how much we loved and missed them.

Last photo I took before he climbed into the truck that would take him to Tijuana.

This year, it was only I who stepped away from the celebration to make that call to Mexico. And for the first time, my dad and I were on opposite sides of the call. I know this will be the reality for a few more years. I wish I could say how many, but I can’t. That is the reality for many undocumented people like myself living in this country.

My dad immigrated to the U.S. when he was 30 years old. In his early 20s, my dad went to college to become a lawyer, but being a father and a student were two things that were hard to balance at that time. He focused instead on being a father. He is now a 47-year-old man, passionate about his guitar and cooking, and still fascinated with law and Mexican history.

Although the relationship between God and me is complicated, my favorite thing to do with my father was to pray together. He would lead the prayer and hold my hand and I just listened and watched him, mesmerized by his faith. My second favorite thing to do with him was to cook. He learned how to cook while in college as he had to leave his hometown and live alone in the city. Once a week I would go over to his house in South Central LA and cook with him while Los Bukis or Brydis would be playing in the background. I miss that now.

I’m glad I have family and friends living with me on this side of the border. I’m lucky enough to have a strong support system and a Christmas and New Year’s dinner to get to, but many other undocumented people do not. Many of us who cannot travel back and forth from our hometown to the US have a tough relationship with time.

As beautiful as annual celebrations like New Year’s, Christmas or birthdays are, they also serve as a reminder and checkpoint that another year has gone by, another 365 days without the people you love. Many of us who have immigrated to this country and are part of the diaspora in this world struggle with the concept of time. We get anxious when we are asked to do any long-term planning because we do not know where we might be tomorrow.

Our immigration status prevents us from knowing if we will be here for another 10 years, or if we can also be victims of deportation at any given time. At the end of every call, my grandmother used to ask me when I would return to Mexico, and I would always tell her it would be sooner than later or that I would be back “in a few more years, maybe two or three more.”

I stopped telling her that. I stopped giving her false hope. She also stopped asking me.

As hard as some days have been without my father, I have also smiled a lot in the last month thanks to the photos and videos my family in Mexico sends me. My first happy moment was just hours after his departure when his sister sent me a video of my father reuniting with his parents at the airport. I know how much my father has longed for an embrace from his mother. He had not seen her in almost two decades when he came to the U.S. alone, a year after my mother and I immigrated here.

He also spent the holidays with his whole immediate family, something he has not done since he left Mexico. San Pablo, the small rural town where my dad was born, also hosts a week-long festival at the end of every year. I remember the many times he told me he had dreamed of this festival and his arrival at this celebration. This year, it was no longer a dream, it was reality.

But not everything has been about festivities for my father in the last month. His health has also been a major priority. My father has diabetes. He was diagnosed in 2021. One of the things that I asked from him was to get a general check-up and find a primary doctor, as all diabetics should have. He did both of these things as soon as he arrived in Mexico and we found out that he has cataracts growing in both of his eyes, caused by diabetes.

Cataracts are cloudy areas in the lens of the eye. “When you have diabetes, high blood sugar (blood glucose) levels over time can lead to structural changes in the lens of the eye that can accelerate the development of cataracts,” according to the American Diabetes Association. My dad described it as looking through a fogged-up window. His doctor explained that, unfortunately, this is a common symptom of diabetes but that his cataracts are so developed that he will require surgery at the end of this month.

I was my father’s caretaker from the summer through the fall of 2021. Going with him to his doctor’s appointments, translating for him and researching his diabetes and medications became a norm. I felt good and calm knowing everything that he needed and what was done for him. I must admit that being away from that, not being there to hear the risks of certain procedures and not being able to have my questions answered by his doctor makes me nervous and worried. The only thing that alleviates those nerves is knowing my aunts and uncles are there to support him.

This month has proved to me two things: that if my dad is OK, I know I will be too, and vice-versa.

Another lesson that I have learned through this travesty is that like me many others are experiencing the same or similar feelings, that my reality is that of many immigrants living in the U.S.

The feelings of sadness, anxiousness and worriedness that come with being away from our families can be solved through equitable and fair immigration reform. Reform that was once promised by President Biden, today feels like a sunk ship, with no intentions to be brought to shore.

My friends and family sometimes ask me how I know I will ever return to Mexico and see my father, I tell them I don’t. I just hope one day I will. I tell them how there are days when I carry uncertainty in every strand of my hair, not even sure I will remember my place around the small, rural town after being gone for too long.

Yet, there are other days when I can feel my father and my grandparents so close, as if we were breathing the same air.

But, on most days. I’m confident the sound of their voices would guide me back – if needed.

(0) comments

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

Keep it Clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexually-oriented language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't Threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be Truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be Nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be Proactive. Use the 'Report' link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with Us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.