CALÓ News reporter, Michelle Zacarias, details her experiences as a recently diagnosed colorectal cancer patient. Image credit: Michelle Zacarias

This past June, I found myself being wheeled into a surgical room for my first colonoscopy. It had been a challenging nine months. From the fall of 2023 up to June 2024, I grappled with a mix of distressing physical symptoms, including diarrhea, bloating, increased gas and alterations in stool consistency.

But It wasn't until I lost 30 pounds in a span of four months, a shocking amount for my five-foot frame, that the severity of the situation set in. Finally, the much-anticipated day for the procedure had arrived. As the anesthesia began to work its way through my body I felt closer to discovering the answers I had been searching for. After all, any news is better than no news, right?

When I finally came to from the sedation, I recall opening my eyes to the room’s bright lights and seeing the doctor standing at the foot of my bed, engrossed in a medical chart. The room was still hazy from the anesthesia, and the nurses gently guided my partner back in. I soon noticed a number of medical staff around me. I struggled to sit up, eager for insight into my situation.

"Did you find anything?" I asked. The surgeon looked up from his paperwork, paused, and said, "We found a tumor."

Right then my world unraveled. I broke down into tears.

I am a 34-year-old colorectal cancer patient and a childhood cancer survivor. This isn't my first encounter with cancer, but it is the first time I’ve had a platform to share my experiences navigating treatment. As a journalist, I felt compelled to explore and address these critical issues. Through this column, the first of many, I aim to investigate the questions that arise and share my findings with others who might benefit from them.

Sharing my cancer journey is both a personal decision and one that I hope will lead to better understanding and open dialogue among community members. The resounding message is clear: seeking early medical intervention is crucial and there is no shame in discussing health problems. I aim to encourage people to take proactive steps toward their health, even if that means seeking answers for myself that may evoke feelings of humility and fear.

As I mentioned previously, this isn't my first encounter with cancer. At age six, I was diagnosed with osteosarcoma, a type of bone cancer. That experience left a lasting impact on me. Chemotherapy was harrowing, with its relentless waves of nausea and overwhelming exhaustion. By age seven, I had lost all my hair and, with it, any trace of a normal childhood. I was often relegated to my hospital room, while my undocumented mother worked multiple part-time jobs.

So much about cancer felt like a sequence of plot twists. In 1997, I underwent a procedure designed to replace the cancerous bone in my leg with a metal one. However, my body rejected the metal implant, leading to a severe infection. In 1999, the infection forced the amputation of my right leg.

Now, 25 years since remission, I thought my battle with cancer was behind me. But there I was in June, diagnosed again.

I started experiencing early symptoms of colorectal cancer as far back as October 2023. My trouble digesting foods that had never bothered me before, such as fried foods, red meats, caffeine and alcohol.

I wrote it off as the growing pains of a maturing woman. My initial oversight was rooted in assuming that these symptoms were just a part of getting older, rather than red flags for a serious condition.

It wasn't until the symptoms worsened that I consulted a healthcare professional. The most concerning sign was a change in my bowel habits, a crucial indicator of the severity of my condition but one that may seem uncomfortable to talk about, particularly among Latino families.

Research consistently highlights that systemic barriers are major obstacles to colorectal cancer screening among Latinos. According to a study by the Colorectal Cancer Alliance, Hispanic Americans are screened at lower rates for colorectal cancer, with only slightly more than 50% of those eligible checked for it. These barriers are rooted in broader issues of access to healthcare and socioeconomic disparities.

Many Latinos face significant anxiety about medical costs. Studies show that uninsured or underinsured individuals are less likely to participate in preventive screenings like those for colorectal cancer. Latinos are also more likely to be uninsured compared to other racial and ethnic groups.

Michelle stands outside of Saint Mary's Hospital in Long Beach prior to one of her delayed surgical procedures. Image credit: Michelle Zacarias

Despite having insurance coverage, I still faced numerous obstacles in accessing efficient and high-quality care. The process was marred by delayed appointments, red tape and a lack of coordination among healthcare providers.

These challenges prolonged the waiting period for crucial treatments and added stress to an already overwhelming situation. Insurance alone doesn't always guarantee better medical care.

After enrolling with a new healthcare provider in December, I struggled to expedite the process for answers. There was a three-month wait for a gastroenterologist appointment. After that, it was another month to schedule a colonoscopy, originally scheduled for two months out but was eventually moved up due to my persistent self-advocacy.

This was the nine-month path to my diagnosis in June.

The emotions and vulnerability I have experienced —the déjà vu to my childhood cancer, the fear and anger – it has all changed my perspective. I have questioned whether I could have done more to safeguard my health, such as heeding to those early warning signs. I have felt deeply disappointed by a medical system that took nearly six months to provide answers when a telehealth appointment could have been a quicker solution.

The American Cancer Society recommends that colorectal cancer screening begin at age 45 for persons at “average risk.” However, the number of young adults under 55 diagnosed with colorectal cancer has nearly doubled over the past decade.

One recent study found that colorectal cancer is the second most common cancer among Hispanic men and the second leading cause of cancer death. Among Latinas, it is the third most common cancer and the third leading cause of cancer death.

But early detection means challenging and dismantling deeply ingrained cultural concepts embedded in Latino culture, including machismo.

In Black and Latino cultures, discussing cancer and other serious illnesses is often seen as a sign of weakness, especially among men. African Americans are about 20% more likely to get colorectal cancer and about 40% more likely to die from it than most other groups. Similarly, Black communities have also faced a rise in people diagnosed under the age of 50. Paired with healthcare inequity, cultural stigma can lead to delayed diagnoses, lower screening rates, and a general reluctance to seek help.

I know this firsthand. After my diagnosis, a relative reached out to tell me about an uncle on my father’s side of the family, Tío Hector, who passed away from colorectal cancer. He was in his late thirties and lived in San Luis Potosi, Mexico. His doctors advised immediate treatment, which would include a temporary colonoscopy bag. Hector's response was baffling to me. He chose to forgo treatment, stating "preferiría morir," or "I would rather die" rather than carry a colostomy bag. He ultimately passed away after a period of heavy drinking.

I’m not my Tio Hector. I’m breaking generational curses, sin pena! Without shame!

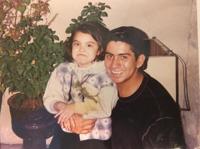

Michelle, age 4, and her Tio Hector in San Luis Potosi, Mexico.

As I write this, I'm recovering from a colorectal resection. The surgery involved extracting a tumor from the upper part of my rectum, but complications resulted in the removal of my uterus, fallopian tubes, and one ovary. This was after two frustrating delays at St. Mary’s Hospital. The first had me waiting nine hours with an I.V. bag before being removed from the surgical schedule. The second delay occurred when I was woken up after being sedated to give explicit consent for the removal of my uterus and any other organs fused to the tumor. Both instances felt like a cruel joke.

In the end, the surgery removed the cancerous tissue and preserved as much of my digestive system as possible. It was a pivotal step in my treatment plan to help identify how to proceed with chemotherapy. I don’t look forward to reliving that experience, but I’m equipped and ready.

With the support of my community, I’m embracing my second cancer journey with optimism and courage, ready to meet the future with unwavering resolve.

(0) comments

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

Keep it Clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexually-oriented language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't Threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be Truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be Nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be Proactive. Use the 'Report' link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with Us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.