CALÓ News reporter, Michelle Zacarias, at six years old holding up a paper-plate turkey she made for Thanksgiving. She was undergoing treatment from 1996-97 for childhood bone cancer.

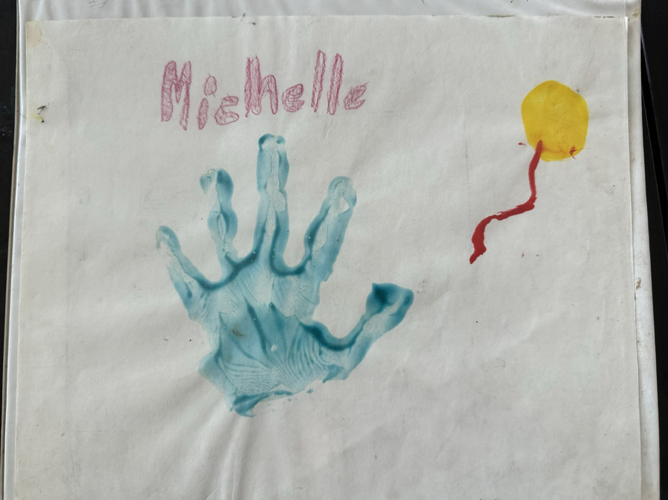

It begins with a simple white three-ring binder, an everyday object that holds a lifetime of memories. A painted blue handprint—my own—adorns its cover, next to my name scribbled in playful red bubble letters. A yellow balloon tied to a string is drawn floating off to the right side of the page.

The cover of the binder, which I decorated as a child, tells a story much more cheerful than the one contained within. Within its pages is a meticulous collection of medical forms chronicling my childhood battle with osteosarcoma, a bone cancer. It traces my journey from the initial diagnosis at age six through years of chemotherapy and, ultimately, the amputation of my right leg. My mother assembled the binder when she was just 22 at the start of my treatment. It became known as my “cancer binder,” a reminder of resilience and the complexities of growing up amid illness.

In June, I pulled this binder back out when I was diagnosed with colorectal cancer – over 25 years after my remission from osteosarcoma. It was stored in the back of a bookshelf, practically forgotten, with the rest of my childhood photo albums. I was searching for clues that might connect my previous cancer experience to my recent diagnosis, which I wrote about in my first column for CALÓ News.

The cover of the "cancer binder," a comprehensive collection of detailed medical forms, documenting my childhood battle with bone cancer. (Image credit: Michelle Zacarias).

Now, this binder has unintentionally become a “guide” in navigating the ups and downs of my current fight with cancer, echoing the challenges I faced during my childhood diagnosis. Despite advances in treatment, I find myself reliving many of the same moments of uncertainty and fear as I navigate the healthcare system.

My recent diagnosis served as a stark reminder of the numerous obstacles that persist within the healthcare system; especially when it comes to early detection. Whereas my colorectal cancer diagnosis took approximately 9 months, my initial diagnosis of bone cancer as a child took over six months.

What began as a slight limp and knee discomfort, quickly escalated to a complete inability to walk. The soreness in my right knee first became noticeable during gym class, prompting my teachers to alert my mother. Over several months, specialists from various fields misdiagnosed my condition or dismissed our concerns. It wasn't until I developed a 103-degree fever and was rushed to the emergency room that an X-ray revealed a large mass in my right leg.

Almost three decades later, I can still clearly recall the day I was admitted to the hospital. The doctor asked me to walk for him, and despite my best efforts, I nearly collapsed to the ground.

The notes in the binder confirm that I was hospitalized on April 3, 1996, but the memories of what followed often seem like a blur. The urgency that swiftly reshaped my life propelled me into a frantic whirlwind of scans and tests, culminating in my first round of chemotherapy.

The “cancer binder” included an in-depth overview of doxorubicin, a chemotherapy drug commonly referred to as the “red devil” because of its vivid hue and harsh side effects. These adverse effects range from hair loss and heightened vulnerability to infections to debilitating nausea and vomiting. I encountered each of these challenges firsthand, feeling the weight of their impact on my body and spirit.

The early stages of losing my hair were brutal, especially as a six-year-old girl. But what stands out even more is my mother shaving off her beautiful full head of black hair in solidarity. For a long time, I clung to a single defiant strand of hair that persisted at the top of my head, a symbol of resistance against the chemotherapy. One day, without hesitation, my mother spotted the lone strand and said, "What is this?" before plucking it. I was devastated.

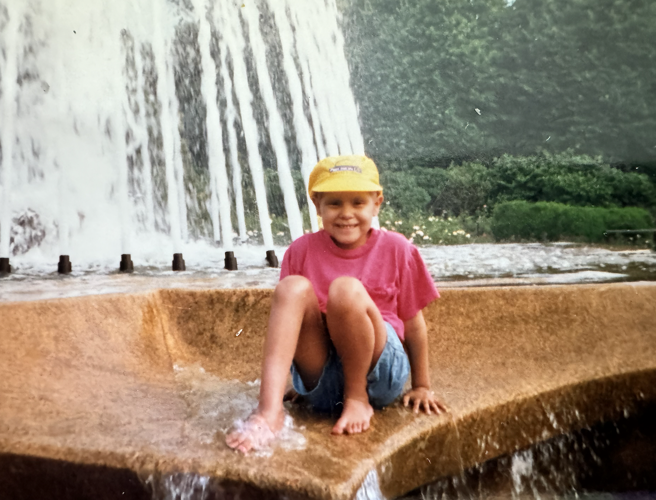

Six-year-old Michelle sits on a water fountain at the Chicago Botanic Garden in 1996, following several rounds of chemotherapy. (Image credit: Michelle Zacarias)

The more superficial aspects of chemotherapy, such as hair loss, faded in significance next to the deeper challenges of treatment. The initial prospects from my first diagnosis were far from bright. Like many children of color with cancer, I faced socioeconomic and racial disparities that pervade our healthcare system.

Research indicates that Latino children are disproportionately affected by cancer, with a higher mortality rate attributed to a range of factors linked to lower socioeconomic status. These challenges often limit access to quality care, delay diagnosis, and lead to fewer treatment options compared to their non-Hispanic white peers. Contributing factors include inadequate health insurance, language barriers, and cultural beliefs that can sometimes hinder people from seeking out early detection resources and preventative healthcare.

My mother, a single parent and undocumented immigrant from Mexico bore the responsibility of my health and well-being. She faced the daunting challenges of navigating a foreign language and an unfamiliar healthcare system. Yet, she was hardly alone in this struggle.

I recall the many young Latino parents we encountered during our hospital visits. My mother frequently stepped in to translate for them, forming connections with families who returned to the hospital. Over time, we became familiar with their faces and stories, and we sensed the gravity of what was often inferred when they stopped showing up.

Michelle and her mother Olga pictured post treatment, 1997. (Image credit: Michelle Zacarias)

Navigating the hospital environment can be incredibly challenging, especially when language barriers are involved. Language concordance in patient care isn’t just a matter of convenience; it’s essential for early detection and accessing quality healthcare. Despite being proficient in English, I still grapple with self-advocacy in healthcare as an adult—the complexities of the system often leave me feeling overwhelmed and uncertain.

Most recently, I found myself in tears on the phone with a healthcare provider, struggling to obtain the correct paperwork for the blood work required before my chemotherapy infusion. Ultimately, it took the intervention of my partner and another doctor to advocate on my behalf.

Despite a lifetime spent navigating hospital settings, I continually face new challenges in articulating my healthcare needs. Each visit underscores the critical importance of patient advocacy, particularly for those who speak English as a second language. This advocacy is vital not just for accessing care, but also for ensuring that patients feel genuinely heard and understood in a system that can often seem impersonal and intimidating.

At 35, I’m increasingly aware of how culture and language profoundly shape our understanding of our bodies and health. Language is not just a means of communication; it carries cultural nuances that influence how we express symptoms, seek care, and navigate medical environments. This interplay can significantly impact our ability to advocate for ourselves and fully grasp the complexities of our health.

It also serves to bridge the gap between our experiences and the care we receive. Despite Latinos representing one of the largest racial and ethnic groups in the United States, only 6% of U.S. physicians identify as Latino/a/e. While more than one-third of physicians report speaking Spanish, this statistic often overlooks the actual proficiency levels among providers.

In some ways, navigating the unknown felt easier as a child. There’s a certain bliss that comes with youthful ignorance. I often wonder if I was braver at six, facing the grueling rounds of chemotherapy with a kind of fearless determination that seems harder to muster as an adult.

This time, I feel fortunate to have the “cancer binder” to guide me through my journey. Although my mother never intended it to be a template for me, it has served a dual purpose in my life. In the weeks following my recent colorectal cancer diagnosis, the binder reminded me that I had faced such challenges before and that I was capable of doing so again. While I may have been a brave six-year-old, I still carry that same determination within me.

(0) comments

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

Keep it Clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexually-oriented language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't Threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be Truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be Nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be Proactive. Use the 'Report' link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with Us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.