Land back.

The rest of it should go without saying, but I’ll say it anyway.

For too long we have relied on unreliable and unsustainable forms of living that are disconnected from nature and connected to colonization. It is time to not only recognize the importance of indigenous practices and decriminalize them, but to also give the land back to indigenous communities that know how to care for the land and learn from their way of life.

After spending two days in the Altadena neighborhoods ravaged by the Eaton Canyon fire last week, I went home feeling defeated, distraught and overwhelmed by the amount of destruction and loss I witnessed. After I decompressed and changed into fresh clothes, I engaged in conversation with my dad, who was watching the evening news in the living room. The segment was on the updates of the fires ravaging through Los Angeles. The news camera focused on the single aircraft carrying water over the fire and dropping it from above. In comparison to the scale of the fire, the water seemed to do little to tame the flame.

My dad watched in amazement, not because he was impressed by the aircraft or the size of the out-of-control fire, but because he was genuinely convinced that if it were up to him, the fires would have been extinguished long before it reached the neighborhoods it burned through.

This scene seemed to send him on a trip to the past – to a time where he was one with the land, manipulating the elements to produce a rich harvest in his family’s riverside ranch.

My father is one of thirteen children who contributed to the daily chores on the small family ranch. My father and grandfather worked tirelessly side-by-side to produce harvests that were not only enough to feed their family, but also enough to share with their neighbors.

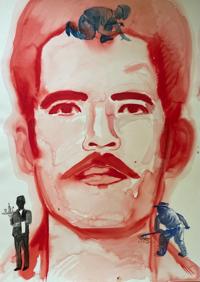

My father’s side of the family is from Guadalajara – a city in Jalisco, the state known as the birthplace of Mariachi and tequila. Jalisco is also known for its deep revolutionary history that is recorded as far back as the year 1540, with The Mixtón Rebellion which formed after the Indian population of western Mexico rebelled against Spanish rule.

During this time, the area that encompassed the state of Jalisco, was known as Nueva Galicia and it also stretched over Aguascalientes, Zacatecas, Nayarit and the northwest corner of San Luis Potosí.

In 1621, Domingo Làzaro de Arregui wrote in his Descripción de la Nueva Galicia, that 72 native languages were spoken in the Spanish colonial province which stretched across 86,733 square miles. Jalisco has an extensive history of indigenous uprisings and rebellions.

What I learned from my father during our conversation last Thursday was that he and his father practiced a type of pseudoscience that worked for them and the land they farmed on. They practiced the indigenous method of starting controlled fires in an effort to produce soil rich with nutrients and free of impurities that would stump the growth of the crops they grew – rice, corn, cucumbers and more.

“When we didn’t want the fire to spread past a certain point in the field, we would create a ring of fire by hitting the line of fire with green shrubbery,” said my father in Spanish.

When they were satisfied with the plot of land that was to be burned, they extinguished the fire entirely and without the use of other resources such as water.

California has a record of several historic fires that have wiped out thousands of square miles worth of land and hurt many communities. Global warming has brought on many challenging years for California such as many record-breaking years of little to no rain, high wind conditions and a landscape that makes it particularly difficult to extinguish larger scale fires.

In 2018, I was living in Lake Elsinore when the Holy Fire broke out in the Cleveland National Forest, a piece of land stretching from Corona to Irvine in southern California. It was the closest I had ever been to what seemed like the opening of a portal to the underworld – prompting evacuations of the small city of Lake Elsinore and the small population living in the forest area.

That same year, the Camp Fire grew into one of the state’s deadliest and most destructive fires on record, devastating the towns of Paradise and Concow in northern California. In 2021, the Dixie Fire raged on for months, ravaging through northern California.

In 2022, The University of California published an article and produced a video about the cultural practice of burning forests.

According to the article, it isn’t just a cultural practice, it is a way to populate the dense forests we see today in places like Yosemite. It is a vital practice to ensure that more vegetation thrive and impurities in the soil are burned to make way for native plants to flourish. According to the article “…ecological records and oral Indigenous history alike describe how fire, sparked by lightning or planned by tribes, played a vital role in shaping California’s landscape for thousands of years.”

In the early 1900’s it was suggested that anyone who started a fire would be shot – a remnant of European rule that regarded cultural burning as primitive or the opposite of civilized.

In September, CalMatters published an article written by Russell Attebery, chairman of the Karuk tribe – a federally recognized tribe overseeing more than 1 million acres of land in Humboldt and Siskiyou counties along the Klamath River.

In the article, he points out that California’s history of out-of-control fires are due in large part, to ignoring the wisdom of indigenous people that have worked for them and the land for thousands of years.

Attebery makes the argument that not only is fire essential to Karuk culture, but that it is also “…not just a tool — it’s a lifeline, a means of renewal, and a vital part of our culture. For generations, our ceremonies have honored the essential role of fire in maintaining the health of our forests, the regeneration of plants and the sustenance of our communities.”

Since the article was published, SB 310 was passed by Gov. Gavin Newsom, acknowledging tribal sovereignty over cultural burning for the first time in California’s history.

This became the first step toward the process of righting historical wrongs and although it is progress, this law only decriminalizes the cultural practice. It does not grant Indigenous people the right to control the land that is rightfully theirs.

(0) comments

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

Keep it Clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexually-oriented language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't Threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be Truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be Nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be Proactive. Use the 'Report' link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with Us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.