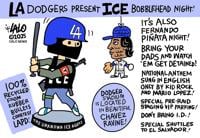

(Graphic designed by Denise Florez on Canva/Getty Images)

President Trump's latest territorial expansion threats are another chapter in a bizarre saga that leaves many baffled. But if you think it’s harmless political theater—a wrestling smackdown for the masses—you might want to reconsider. The threat of a U.S. invasion of Mexico is nothing new. After losing half its territory in 1848, Mexico endured decades of U.S. threats, aimed at keeping it underfoot. But these are different times, and Mexico may have a surprising secret weapon to counter any attempts at a Manifest Destiny redux: the chancla.

President Trump seems eager to resurrect ideas that harken back to a time when Americans embraced perceived divine favor. For Trump, the "city on a hill" rhetoric is rooted more in real estate rivalry with Putin than morality. It’s a distorted nod to a bygone era—an inflated view of American greatness. Even worse, this Trumpian geopolitical stance isn’t about strategy; it’s about ego. If Putin claims part of Ukraine, Trump wants his slice of Mexico, Canada, Greenland or even Panama. It’s not driven by purpose but a competitive display of dominance.

The U.S.-Mexico relationship has always been complex. During the U.S.-Mexican War (1846–48), the U.S. fabricated an excuse to invade Mexico, seize half its territory and claim moral superiority by "paying" for the land. Debates over slavery halted further expansion, while other leaders viewed Mexico's Indigenous population as a problem. If 19th-century leaders considered Mexicans—stigmatized as Indians, mongrels and vagabonds—a problem, Trump and his allies might need to rethink their assumptions. Contrary to popular beliefs at the time, Mexicans did not fade into obscurity; instead, they multiplied and thrived.

For over a century, the U.S. sought to dominate Mexico’s economic and political development. It was done through both soft and hard diplomacy. For example, the U.S. often backed Mexican elites trained in American institutions. These elites promised American-style democracy while catering to U.S. economic interests. Mexico’s role was clear: to provide cheap labor and assemble goods for U.S. export. Innovation or economic competition from Mexico was neither expected nor encouraged.

At other times, direct American intervention was needed to correct Mexico’s “bad” behavior. The Mexican Revolution, from an American standpoint, was “bad” for business. The machinations of Ambassador Henry Lane Wilson aside, the direct use of U.S. forces to kill or capture Francisco “Pancho” Villa, a one-time ally, is telling. The mission should have been simple until it wasn't. In 1916, President Wilson sent General Pershing and 6,000 troops into Mexico after Villa’s attack on Columbus, New Mexico. To Americans, Villa was a bandit, but to Mexicans, he was a hero standing up to the colossal north. Mexicans protected Villa, and Pershing’s troops chased shadows. Villa survived because the population supported him.

Fast forward to today. While Mexico has endured violence from its drug wars, Trump’s threats to send troops or missiles into Mexico ignore key realities. The fight against fentanyl isn’t centralized. The DEA has found that fentanyl trafficking involves diverse sources and routes, including China, India and Canada. U.S. ports, FedEx, UPS, the dark web, and social media are key points in its distribution. Indeed, U.S. financial institutions facilitate the movement of funds for fentanyl networks. In normal times, a multipronged approach—one that includes collaboration with allies, incentivizes cooperative policies and focuses on health and stability—might rise to the top as the best course of action. But these aren’t normal times.

Fentanyl is a tragedy, devastating families and communities on both sides of the border. However, sending troops into Mexico would be a dangerous misstep. While the U.S. military might overwhelm that nation’s resistance, it would be a mistake to view this as a win over Mexico. Mexico is the U.S.'s largest trading partner, with over $250 billion in annual trade, supporting millions of U.S. jobs. Its economy is deeply intertwined with global markets and trade networks, making its stability and prosperity vital to international economic health. Ignoring this interconnectedness risks disrupting supply chains, harming U.S. businesses and undermining broader geopolitical relationships. This is not to be ignored.

And yet, the elephant in the room—hiding in plain sight—remains ignored: guns. Specifically, American-made guns. According to an ATF report, 74 percent of guns seized in Mexico were smuggled through Southwest ports. The report concludes that if the same enforcement used for domestic trafficking were applied at the border, illegal firearms would decrease significantly. Mexico argues that such measures would profoundly impact efforts to control violence. This concern led Mexico to take its case to the U.S. Supreme Court in October 2024, where it is currently under review.

If history is any guide, Mexico will never agree to U.S. troops entering its territory. Such action would force the U.S. into an occupation met with widespread resistance—not from Mexico's military, but from its people. Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum, elected with 59 percent of the vote and enjoying 70 percent approval, commands significant legitimacy. Her government could rally protests across cities, turning any occupation into a public relations disaster for the U.S. In this scenario, Sheinbaum wouldn’t need weapons—just metaphorical sandals (“chanclas”) to hurl at American soldiers as a powerful symbol of defiance.

The lesson from history is clear: invasions rarely go as planned. And the lesson closer to home isn’t too different: Actúa como un pendejo y cuídate porque ya viene el chanclazo. In other words, act like a fool and watch out—the chanclazo is coming. Mexicans gave General Pershing a resounding chanclazo, and the result was his retreat with his tail between his legs. Our mothers’ chanclas were incredibly effective: they taught us not to be pendejos.

(0) comments

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

Keep it Clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexually-oriented language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't Threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be Truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be Nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be Proactive. Use the 'Report' link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with Us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.