The Trump administration is aggressively pushing self-deportation for undocumented immigrants living in the U.S. Part of that strategy involves stoking fear in communities through highly publicized enforcement activities.

But legal experts say, despite government assurances, the risk to those who do self-deport can be significant.

“Once they’re gone, they might be stuck on the outside for years, or it could be forever,” says Professor Gabriel “Jack” Chin, director of Clinical Legal Education at the University of California, Davis School of Law.

Often, Chin says, individuals in this situation have accrued a period of unlawful presence in the United States, which, after leaving the country, can trigger a multi-year or even permanent ban on reentry. Consular officers, meanwhile, have broad discretion to deny future visa applications based on that history.

Anyone thinking about self-deporting should first consult with an immigration attorney or a reputable nonprofit organization that specializes in immigration law, stresses Chin. There may be legal avenues to remain in the country, especially for those with U.S. citizen relatives or individuals who unknowingly hold U.S. citizenship through a parent or grandparent.

Many nonprofit organizations, such as CHIRLA, Catholic Charities, ASOSAL, CARECEN, the San Bernardino Community Service Center, and the Amica Center, among others, provide free or low-cost legal services to immigrants.

‘Scare a million people a year’

According to the Department of Homeland Security’s Project Homecoming website, undocumented immigrants who “self-deport” under the program can receive assistance in the form of a plane ticket, a $1,000 exit bonus, and forgiveness of fines for “failing to timely depart.”

Russell Jauregui is an attorney at San Bernardino Community Service Center, which supports immigrants with legal services and education. He says such statements, echoed in official ads running on local stations that promise, “If you leave now, you may have an opportunity to return,” offer a sense of “false hope” to communities experiencing fear and uncertainty over ongoing immigration raids.

“I think the administration is relying on self-deportation. In other words, I don’t think they can arrest and deport a million people a year… but they can scare a million people a year,” explains Professor Hiroshi Motomura, faculty co-director at the Center for Immigration Law and Policy at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA).

ICE arrests have surpassed the 100,000 mark during Trump’s second term, with pressure on the agency to meet a goal of 3,000 arrests per day nationwide.

It remains unclear how many have participated in the Project Homecoming program. A DHS press release in May suggested some 64 individuals had chosen to be returned to Honduras and Colombia. Mexican officials reportedly confirmed that a small number of those detained in recent raids in Los Angeles opted to self-deport rather than face extended detention or removal proceedings.

The administration also recently deported several individuals to the small African nation of Eswatini. The five men hail from Vietnam, Jamaica, Laos, Cuba, and Yemen.

For Motomura, such tactics are part of a broader strategy. “It’s really a central feature of the administration strategy to scare people and then to get people to leave on their own,” he says.

‘Why don’t you just go to jail?’

Amelia Dagen is an attorney with the Amica Center, which provides legal representation to immigrants. She told The Marshall Project that government materials once used to share information about legal services are now being replaced by posters promoting self-deportation.

Such pamphlets are not only posted in detention centers, she says, but also appear in courtroom lobbies, and are even passed out with official court documents.

Advocates say the effort is part of a strategy to discourage people from seeking legal assistance. “They’re trying to lock as many people up and they don’t want them talking to attorneys,” says attorney Nicholas Mireles, who has been representing immigrants for more than twelve years. “They don’t want them, you know, asking about their rights.”

The whole approach undermines due process, insists Mireles, offering the analogy of someone in criminal proceedings being told by the court, “Instead of going through the trial and witnesses and having the government prove their case, why don’t you just go to jail?”

Still thinking of self-deporting?

For those still contemplating self-deportation, Chin says they should gather and preserve key documents that may become essential later on, especially if they hope to return or apply for legal status in the future. Financial records—such as tax returns, pay stubs, or any proof of tax payment—can be especially important, as some legalization programs require evidence of tax compliance.

Similarly, proof of residence is often a critical component in immigration cases, so items like utility bills, rental agreements, or lease receipts should be collected to demonstrate sustained residence in the U.S. Chin also emphasizes that individuals leaving the country should carry official documentation for any U.S.-born children or relatives traveling with them, including birth certificates and passports.

“It might not make a difference right now,” he admits. “But over the years, various kinds of proposed and actual legalization programs have depended on a certain period of residence in the United States, and so it could become relevant in the future.”

For those who own property, a power of attorney can be essential. More urgently, for anyone leaving behind children or dependents, it’s vital to ensure proper legal custody arrangements are in place. Each state has different laws, but generally, someone must be legally designated to make decisions regarding a child’s education, medical care, and day-to-day needs.

In many cases, appointing a legal guardian is the appropriate step, and it may require formal legal proceedings.

Chin warns that those preparing to self-deport are still susceptible to law enforcement if they have pending criminal cases or outstanding warrants. In such situations, consulting a criminal defense attorney beforehand is critical, he says.

Seek help and don’t jump to conclusions

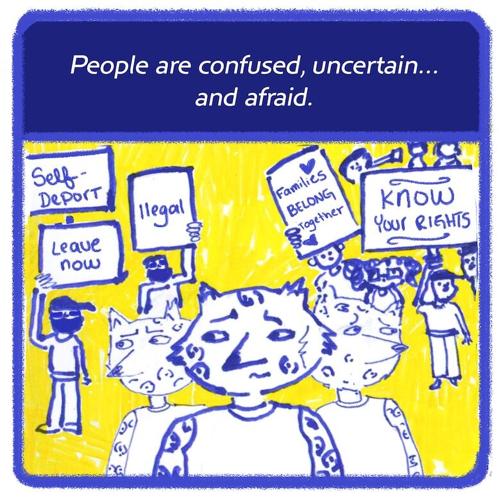

In moments when confusion and fear feel overwhelming, reaching out can be the most important first step, explains Mireles.

While resources are stretched, trusted networks—whether a church, school, or community organization—can offer guidance at no cost. “Information is power,” he notes, adding that the hardest part is often finding the courage to ask for help.

“People just have to try not to jump to conclusions or make life-changing decisions all of a sudden,” he advises. “Maybe waiting and seeing and giving it a week, giving it a month that day-by-day approach may be the best thing they can do for themselves and their family.”

He adds, “I think the point of everything these days is to overwhelm people so much so that they just give up. But, like anything in this world, when you feel that way… that’s when you have to really dig down deep and ask for help.”

Feature image published under CC License 1.0

This story is part of “Aquí Estamos/Here We Stand,” a collaborative reporting project of American Community Media and ethnic/community news outlets statewide tracking how current White House policies are impacting Californians, especially in rural regions, and how residents are responding.

(0) comments

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

Keep it Clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexually-oriented language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't Threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be Truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be Nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be Proactive. Use the 'Report' link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with Us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.