An LAPD officer on horseback swings a wooden baton at protesters at the “No Kings Day” protests on June 14, 2025. Credit: Héctor Adolfo Quintanar Pérez

This story is part of ICE vs. LA, a collaborative reporting project by LA Public Press, Caló News, Capital & Main, Capital B, LA Taco, and Q Voice. The newsrooms worked together to report what actually happens when immigration enforcement arrives — how people mobilize, look out for each other, and try to keep their families intact. Read more from the collaboration here.

On June 14, journalist Héctor Adolfo Quintanar Pérez was on a freelance assignment photographing the “No Kings Day” protest in Downtown Los Angeles for Zuma Press. For days, hundreds of people had come out in a series of protests to voice their anger in response to an escalation in federal immigration raids that had swept up hundreds of immigrants in Southern California.

It was Pérez’s first time reporting in the United States, but he wasn’t too worried. A seasoned conflict reporter, Pérez had witnessed his fair share of dicey situations while reporting all over the world, from his home country of Mexico to the war in Ukraine.

In some videos of Los Angeles over the spring and summer, protesters were seen throwing rocks and Lime scooters on law enforcement vehicles and Waymo cars were set on fire. But Pérez said most of the protestors he observed were exercising their First Amendment right peacefully.

“It was maybe a little bit tense, but without any issue or really any provocation,” Pérez recalled that day of the “No Kings Day” protest, as protestors shouted insults at stoic Los Angeles Police Department officers. But in the early evening, the energy shifted dramatically.

“The LA police arrived with this little tank and with the horses. And that’s when everything lost control,” he said.

A journalist wearing a helmet marked “PRESS” holds a phone in their left hand to record video as they hold a camera with the right to take photos as LAPD officers advance toward protestors on horseback during the “No Kings Day” protest in LA on June 14, 2025. (Credit: Héctor Adolfo Quintanar Pérez)

Facing toward the police, Pérez said he did not waver and kept his finger steady on the shutter of his camera snapping photos as protestors were pushed back with force. Pérez snapped a shot of an officer, the name “Del Gadillo” spelled out on his helmet, as he was shooting tear gas canisters into the melee.

Héctor Adolfo Quintanar Pérez photographed a Los Angeles Police Department officer shooting tear gas canisters. Perez was hit by a canister moments later. (Credit: Héctor Adolfo Quintanar Perez)

A second later — BANG. Perez said he crumpled with a sharp pain in both his knees, coughing as he realized he had been shot with a tear gas canister that ricocheted off both his legs. Pérez was left bloodied and he said it was the officer he had just photographed who had taken aim at him.

“I think I was targeted by the police,” Pérez said. That day he remembered he had a visible media badge and was carrying two large cameras while wearing protective gear. “It was obvious that I was part of the press,” he said.

Héctor Adolfo Quintanar Pérez was injured by a tear gas canister that ricocheted off his knees. (Courtesy of Héctor Adolfo Quintanar Pérez)

Pérez, along with other journalists who allege they were targeted by police, filed testimony in a lawsuit brought by the LA Press Club against the LAPD in the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California. In court filings, the City of Los Angeles objected to Perez’s account, stating he was not targeted as police dispersed the crowd and that the photo taken by Pérez “clearly shows that the officer was not aiming at him.”

Freelance journalists navigate lawsuits and confrontations with law enforcement —often without institutional support

As immigration raids have swept Southern California, freelancers like Pérez and unconventional citizen journalists have often been the first to the scene documenting ICE sweeps and the protests that follow in their communities. Sometimes, that comes at a personal cost. Tiktoker Carlitos Ricardo Parias, well known for tracking and posting footage of ICE raids, himself was targeted by federal immigration authorities and shot while being detained. Earlier this week, the Fullerton Police Department said an ICE agent pulled a gun on a woman who was recording him.

Pérez was one of dozens of journalists who were injured this summer while documenting anti-ICE protests across LA, according to numbers tracked by The U.S. Press Freedom Tracker, a project of the Freedom of the Press Foundation. Their reporters track press freedom violations across the country by combing the internet and interviewing journalists who’ve been targeted.

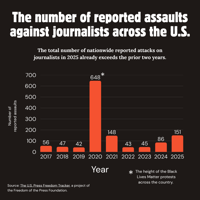

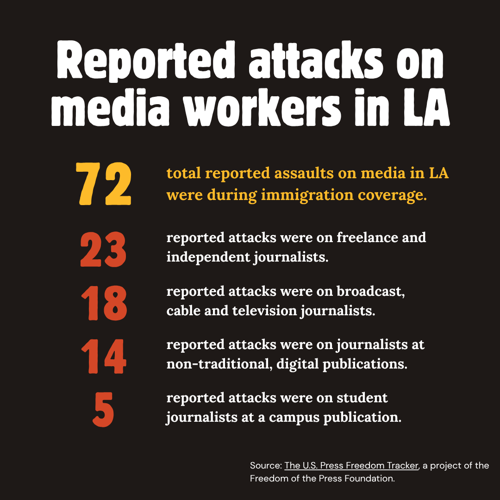

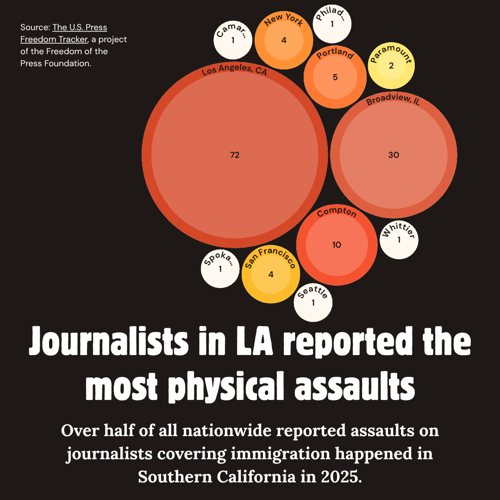

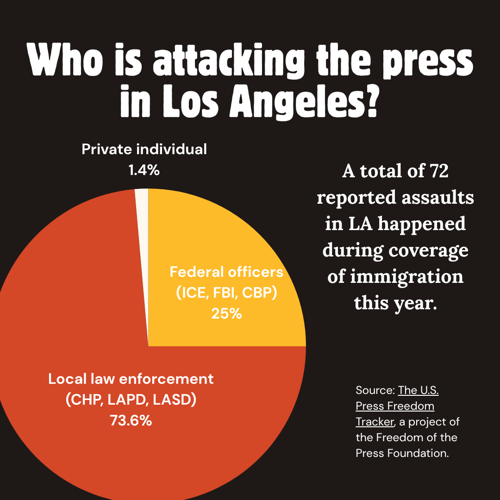

The U.S. Press Freedom Tracker has documented 151 physical attacks against media workers in the U.S. this year alone — more than the last two years combined. Of those, 72 were related to immigration coverage in LA. Even during the peak of the Black Lives Matter protests in 2020, when 648 journalists reported assaults to the tracker, only 33 of the attacks occurred in LA that year.

Susan Seager, a law professor at UC Irvine and the head of the Press Freedom Project, is concerned about these physical threats toward journalists.

“I don’t think I’ve ever seen this many reporters hurt by the LAPD before,” said Seager, who is one of the attorneys representing the Los Angeles Press Club in its lawsuit. “It’s much more widespread and more violent than I’ve seen in 25 years.” Captain Mike Bland of the media relations division of LAPD said the department could not speak to the total number of assaults against media in Los Angeles over the summer and that they do not track use of force by other law enforcement agencies.

Credit: Jireh Deng

According to Seager, journalists aren’t protected by their affiliation. She said the attacks have hit all types of reporters, from those employed by the Los Angeles Times to lesser known freelancers. One group, however, according to her, takes on a lot more risk and is more willing to fight back.

“The big media organizations don’t get involved in these lawsuits,” Seager said of the reporters who she said want to stay neutral and maintain relationships with law enforcement.

Some reporters from mainstream media outlets also faced press freedom incidents this summer. An Australian reporter was on live television when shot in the leg by a rubber bullet, a New York Times reporter was hit by a foam projectile in the abdomen and a CNN crew was briefly detained and escorted away from a protest. A New York Times representative said that they are not involved in any litigation against LAPD.

“The freelancers, the independent journalists, the nonprofit journalists, are the ones who actually have the courage to sue,” Seager said.

Seager said she helps many of her clients on press freedom issues pro-bono because, as freelancers, they cannot afford legal representation. Freelance and independent journalists were the largest group of individuals who were physically assaulted by police this summer, according to the numbers reported by The U.S. Press Freedom Tracker.

Freelancers are taking on more personal and financial risks

Credit: Jireh Deng

Melanie Buer, a freelance journalist who has previously reported for LA Public Press, was detained for 90 minutes and zip tied by the LAPD alongside other colleagues on Aug. 8 while live tweeting immigration protests outside of the Edward R. Roybal Federal Building in Downtown LA.

“90% of the work that I do is unpaid at this point. I do it because I care about it,” said Buer, who’s been freelancing since April when she was laid off from her job at the Real News Network. “I’m navigating unemployment benefits and SNAP and struggling to get a newsletter off the ground.”

Buer said she’s part of a growing cohort of journalists who are being forced into precarity as the industry continues to shrink and stable jobs are fewer and more competitive.

“Half the freelancers I know don’t even have health insurance,” Buer said. Freelance journalists also take on significant physical risk to cover protests without the institutional backing a staff reporter would have. “There is no workers comp [if we get injured.]”

While reporting on immigration protests in LA on Aug. 8, 2025, Melanie Buer was zip tied and arrested. Credit: J.W. Hendricks.

The same day Buer was arrested, an LAPD officer hit freelancer Sean Beckner-Carmitchel with a baton, fracturing his ribs. Beckner-Carmitchel was reporting a story for LA Public Press when he was injured. He said he was unable to work and was forced to take time off for three weeks in order to heal. LAPD’s Bland said the department cannot comment on active investigations of an officer’s use of force, but that officers are held to “the highest standards.”

“The scary thing about taking time off when you’re a freelancer is that means you’re not making any money,” Beckner-Carmitchel said. His most recent visit to the doctor marked his 10th hospitalization while reporting on civil unrest in the past five years.

“It’s a constant battle to make sure that you’re working enough to make money, but not working so much that you completely and utterly burn yourself out,” he said. Adding to his financial stress, Beckner-Carmitchel said he was delayed payment on several freelance stories and worried about his ability to cover bills over the summer.

Photographer Solomon O. Smith said freelancers are often expected to work without guarantee of pay when it comes to documenting protests. “You’re kind of working for free until you sell [pictures],” he said.

Smith was also photographing the clash between protesters and police during the “No Kings Day” protests on June 14 when he was struck several times by crowd-control munitions. The day he was shot, he said his laptop was dented. And he had a bruise on his rear and back for several weeks.

Ethan Cohen, a student-journalist with the Long Beach Current, the news publication for Cal State Long Beach shows injuries he received during the No Kings protest in June. He said he was clearly marked as a journalist when he was struck by police with less-lethal ammunition (Credit: Solomon O. Smith)

“A lot of these police officers don’t always see me as a journalist,” Smith said. He said he’s seen his white colleagues treated differently and believes that as a Black man, law enforcement often profile him as a threat. “When you’re a Black or brown photographer, and you don’t have a big media outlet to cover you, expect that it’s going to be more dangerous for you, ” he said.

With the decentralization of news and rise of citizen journalism, police are questioning the credibility of freelance journalists, said Stephanie Sugars, a senior reporter at the U.S. Press Freedom Tracker. Sugars said she has heard of officers across the country, including in LA, characterizing independent journalists as “fake press people” who “parade as members of the media.”

“There’s no basis for that, as far as I have seen in my work,” she said.

LAPD media relations officer Bland alleged that over the summer, several officers witnessed “bad actors” posing as media ”acting and behaving in a way that was assaulting our officers,” but Bland was not able to provide specific examples of these incidents.

Los Angeles is ground zero over the fight for a free press

The Los Angeles Press Club is now suing on behalf of battered and harassed journalists, including Beckner-Carmitchel, in three lawsuits against the LAPD, the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department and the Department of Homeland Security. The complaints allege that federal and local law enforcement officers violated the First Amendment rights of journalists in “using excessive force” against them.

Local law enforcement agencies, including California Highway Patrol, LAPD, LASD, were responsible for most of the reported assaults against journalists this past summer, according to LA Public Press’ analysis of The U.S. Press Freedom Tracker’s data. The assaults included incidents of reporters being shot with less-lethal munitions and being shoved by law enforcement officers.

LASD did not respond to LA Public Press’ media request. But the County’s formal response to the lawsuit in September states that “any injury or damage suffered by plaintiffs were caused solely by reason of plaintiffs’ wrongful acts and conduct and the willful resistance to a peace officer in the discharge.”

Credit: Jireh Deng

Reporters faced similar challenges while reporting on protests during the Black Lives Matter movement of 2020. In response, media advocates pushed to pass Senate Bill 98 in 2021, a California law that expanded the protections of journalists to continue reporting on protests after dispersal orders are given to the public.

In September, U.S. District Judge Hernán D. Vera issued a preliminary injunction to bar the LAPD and federal law enforcement agencies from using excessive force against members of the press. In response, City Attorney Hydee Feldstein Soto filed an appeal to halt the injunction to allow LAPD to continue using force against journalists — a move that city council members unanimously voted against earlier this month. The City Attorney’s office did not respond to LA Public Press’ request for comment.

Both the City of Los Angeles and DHS have opposed Vera’s injunction. The city’s opposition states that it “poses a risk to public safety and officer safety.” The brief filed on behalf of DHS last month calls the injunction “overbroad and unworkable,” and states that the definitions of protesters, legal observers and journalists are “vague.”

Credit: Jireh Deng

In a press statement released last Monday, LAPD said the injunction impedes on its officers’ “ability to manage the complexities of unlawful assemblies and unruly crowds” saying that restrictions on less-lethal munitions prevent effective crowd control and that ambiguity around who qualifies as media puts law enforcement at risk.

Why does press freedom matter?

From Beckner-Carmitchel’s perspective, the fight to recognize the legitimacy of freelance journalists is about acknowledging that everyone has a First Amendment right to document the activities of law enforcement. He said his career as a journalist began in earnest in the summer of 2020 when he was out on the streets documenting the mass protests against George Floyd’s murder.

“We found out about what happened to George Floyd, not because of someone from a major news agency filming it,” he said. A Pulitzer Prize was awarded to a teenager that year. “It was a 17-year-old Darnella Frazier. She filmed it on her cell phone.”

Jen Golbeck photographed the moments after a protester in LA on June 11, 2025 apparently threw a soda can at law enforcement. Golbeck said one or more LASD deputies then shot at him with a less-lethal munition at close range. (Credit: Jen Golbeck)

Adam Rose, the press rights chair of the LA Press Club and deputy director of advocacy for the Freedom Press Foundation, said everyone, not just journalists, should be concerned about press safety.

“We don’t have a democracy without an informed public. We don’t have an informed public without a free press,” Rose said. He believes that if the police start to dictate who has access to report on protests, it could undermine police accountability and lead to further “abuses of power.”

(0) comments

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

Keep it Clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexually-oriented language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't Threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be Truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be Nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be Proactive. Use the 'Report' link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with Us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.