(From left) Robin Young, Christopher Garcia, Alisha Vasquez and Marian Holland laugh as they talk about their childhood growing up on Tucson’s south side during a tile-making workshop to commemorate those who died from TCE contamination. (Stephanie Casanova / CALÓ News)

Tucson, Arizona – Robin Young sat at a table surrounded by four of her lifelong friends. They reminisced about their childhood when they ran around in the vacant home next to hers until Marian Holland moved in.

The group of friends lived on Tucson’s south side, just south of Valencia Road near 12th Avenue, in the 1970s. They’ve been there for each other through many of life’s milestones and supported one another through loss and grief.

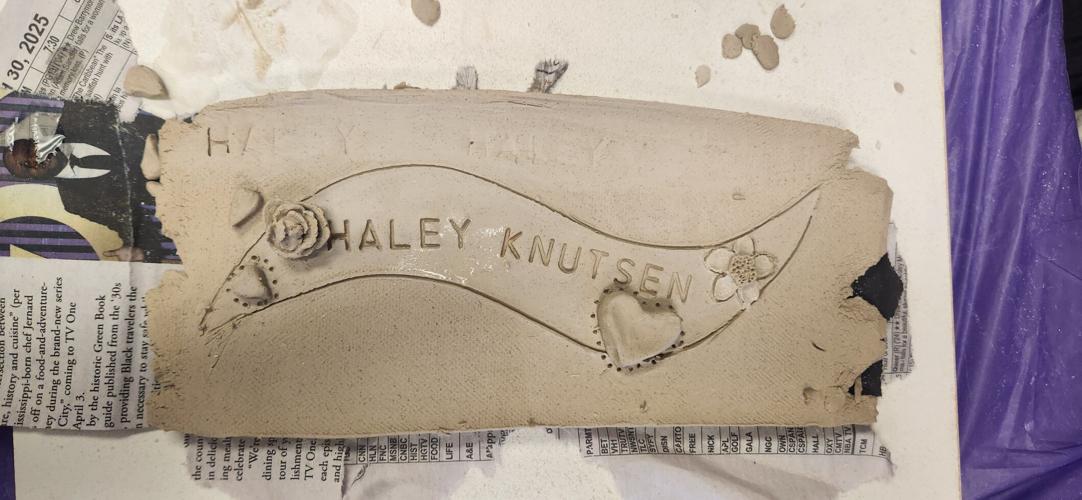

On Saturday, they leaned on each other for support once more as they commemorated loved ones who died of illnesses due to contaminated water on Tucson’s south side. As Young and her friends shared childhood stories, her daughter sat next to her adding finishing touches — a heart and a flower — to a tile with the name Haley Knutsen etched into the clay. Knutsen, the daughter of another friend of the group, died when she was a little girl, Young said.

Christina Ortega Thomas had just finished carving her father’s name on a wave-shaped clay tile. Christopher Garcia made a tile with his wife’s name on it and Holland carved her mother’s name, Mary Lemon, into a tile.

In the 1950s, Hughes Aircraft discharged trichloroethylene (TCE), an industrial solvent, into areas of South Tucson and Tucson, including the neighborhoods south of Valencia Road. The pollution resulted in many Tucsonans getting cancer and other rare illnesses from drinking the water until the wells were closed in 1981.

The workshop was the last one, but a series of other events are planned to honor those impacted by TCE contamination. The tiles will all go into a mural at Mission Manor Park later this year.

“This is a chance for us to all acknowledge that we went through something together, and we've been suffering from trauma for all these decades,” Young said. “There's a community that suffered.”

Her voice caught as she held back tears.

“And by coming together, we can heal each other and ourselves, and we're finally able to say out loud, TCE killed my mother, TCE killed my father. TCE killed my brother, my wife, my, you know, my sister, my child.”

Community members from Tucson's south side create clay tiles with the names of people who died due to water pollution. Haley Knutsen died when she was a little girl due to health complications from the TCE contamination. (Stephanie Casanova / CALÓ News)

A story about ‘surviving and resisting’

For decades, south side residents drank polluted water unknowingly. Children as young as five died of leukemia and teenage boys were diagnosed with rare cases of testicular cancer. Residents suffered from neurological complications, several types of cancer and heart defects.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) tested water wells in 1981, confirming that TCE levels exceeded EPA limits, leading the Pima County Health Department to close all polluted water wells.

A 1985 Arizona Daily Star investigative series by journalist Jane Kay publicly confirmed what Tucson’s south side communities had known for years.

Forty years after that investigation, Alisha Vasquez, co-director of the Mexican American Heritage and History Museum, and Sunaura Taylor, author of “Disabled Ecologies: Lessons from a Wounded Desert,” are hosting events to honor those who died from the polluted water as well as the people who fought for justice. Taylor grew up on Tucson’s south side and both she and Vasquez were also impacted by the contamination.

“Ultimately, this is a story about the community,” Vasquez said. “This is a story about literally surviving and resisting.”

“Survival and Resistance: Remembering the Southside’s Environmental Justice Movement” is a yearlong commemoration that includes museum events, workshops and a mural in honor of those affected by TCE contamination.

Vasquez has talked to her family about her work with TCE since she and Taylor started planning the commemoration in 2021, but she didn’t know she had family members who had been affected. In 2023, months after her grandmother died, her aunt called her to tell her she found Vasquez’s grandfather’s lawsuit paperwork. That’s when she learned her grandfather was a plaintiff in one of many unsuccessful lawsuits against Hughes Aircraft.

“The fact that I didn't know that, and my Nana just didn't say anything to me speaks to that pain and the silences that exist in our communities for survival,” Vasquez said.

The community-decorated tiles will be displayed on the backside of an existing mural wall that currently commemorates Tucsonans who died of COVID.

The artist behind both murals, Alexandra Jimenez, who goes by the artist name Alex!, has incorporated water into her artwork for many years. Along with the wave-shaped tiles, the mural will include milagros — small charms that people in Mexico and Latin America often place on altars. Jimenez showed CALÓ News small clay limbs, breasts and other body parts that represent the many areas of people’s bodies that were affected by contamination. The mural will also depict water trickling down into the groundwater with a human form.

She said it’s essential that people who were impacted have a permanent place that acknowledges what happened to them and their families.

“Acknowledgement is a huge part of validation, validation that it happened, that their pain and loss is real,” Jimenez said. “Memorials really help with that.”

Christina Ortega Thomas poses for a photo with a clay tile bearing her father’s name. Her dad, Ramon Ortega, died of kidney cancer in 1972. (Stephanie Casanova / CALÓ News)

‘He didn’t get to enjoy his retirement’

It was Young’s second tile-making workshop on Saturday. At her first workshop, she made a tile to commemorate her mother who died in 1985 of multiple myeloma, a blood cancer that affects plasma cells, the white blood cells that produce antibodies. It’s a cancer that until that point had only been seen in older Black men, Young said.

Her mother, a white, middle-aged woman, was diagnosed in 1979. She started showing symptoms of illness much earlier, in 1974, when X-rays revealed a fracture in her ribs. By 1979, her white blood cells “basically ate her bone marrow,” Young said. She also had a hip replacement and went through six years of chemotherapy on and off.

Young was 21 when her mother died.

“My mom’s name will live beyond my life,” she said. “She got robbed of a life.”

Ortega Thomas’ father, Ramon Ortega, was diagnosed with cancer in his kidneys in 1972, when he was 57 years old. His kidneys were removed and he went through dialysis treatment. After years of battling the illness, her father told the family he was done with dialysis, Ortega Thomas said. Two weeks after ending his treatment, he died at age 72.

“He worked very hard and then was diagnosed with kidney cancer,” Ortega Thomas said. “He didn't get to enjoy his retirement.”

His lawsuit was settled more than a decade after his death. Being able to memorialize him with a tile has been a blessing, she said.

Christopher Garcia met his late wife, Liz Matiella Garcia, in his sophomore year at Sunnyside High School. They were high school sweethearts and would go on to get married and have two children. She died of ovarian cancer in 2013.

In her biopsy, the illness was traced to talcum powder contamination, but Garcia believes she was also affected by the TCE pollutants in the water she drank growing up.

“We are angry because of how it happened,” he said. “We're angry also, because we lost that loved one that’s never coming back, and then we have to adjust our lives to it again, all because, you know, we became the subject matter of an industry that totally took advantage of the poor communities.”

The workshop and the mural are providing some form of healing, Garcia said.

“I think it memorializes those that we love who impacted our lives, as friends, relatives, you know, grandmothers, grandfathers,” he said. “I think it's a great way to keep the community together, and it's also a great way to never let anybody forget what we went through, and hopefully to never let it happen again.”

Stephanie Casanova is an independent journalist from Tucson, Arizona, covering community stories for 10 years. She is passionate about narrative, in-depth storytelling that is inclusive and reflects the diversity of the communities she covers. She recently covered the criminal justice beat at Signal Cleveland, where she shed light on injustices and inequities in the criminal legal system and centered the experiences of justice-involved individuals, both victims and people who go through the system and their impacted loved ones.

(0) comments

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

Keep it Clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexually-oriented language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't Threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be Truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be Nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be Proactive. Use the 'Report' link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with Us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.