Image credit: Ben Camacho

In September of 2022, Ben Camacho sat in his car outside of Los Angeles City Hall awaiting a thumb drive. The independent Knock-LA reporter and photojournalist spent months going back and forth with the city before he filed a lawsuit for access to public records requested in 2021. The initial filing asked for the most up-to-date roster of Los Angeles Police Department officers, including headshots, names, badge numbers, serial numbers, division, and sworn status – all information Camacho assumed would be made available to the public.

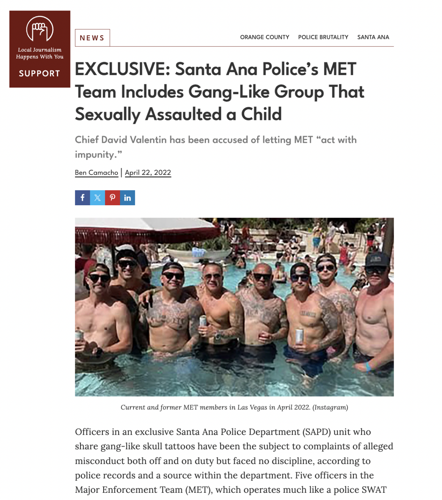

Camacho’s previous work as a reporter has primarily focused on investigating instances of police misconduct. In 2022 he wrote an exclusive for Knock L.A. about Santa Ana’s “secret police force,” the Major Enforcement Team (MET). In 2020 a group of off-duty Santa Ana Police officers associated with the gang-like unit were witnessed verbally and physically harassing two teenage girls in Santa Ana. Camacho was able to identify the officers at the scene through the information he obtained from a public records request.

Later that year in October of 2021 Camacho said he was reviewing more cop-watch videos for another story, except this time looking specifically at LAPD. “I noticed this pattern from the LAPD” Camacho told CALÓ News reporter, “whenever they were asked to identify or say their badge number they refused to, or they danced around the question.”

After the positive response he received on the Santa Ana Police Department exposé, Camacho realized there was a gap in police misconduct reporting. “As an investigative journalist, if you don't know who you're investigating,” he said, “then you're missing a crucial point in your research.”

Screenshot of Camacho's article on the Santa Ana Police department that was published in April 2022. Image credit: Knock L.A.

Camacho first received pushback on his public records request for the city after the LAPD insisted that the photos of officers would have to be digitized, which was a task that they felt fell outside the scope of their obligations to the public.In a message dated November 4, 2021, The LAPD Public Records and Subpoena Response Section, California Public Records Act Unit stated: “The public’s right to access must be balanced against such weighty considerations as the right of privacy, a right of constitutional dimension under California Constitution, Article 1, Section 1.”

To access the database of LAPD officers, Camacho was forced to file a lawsuit, which he says set off months of negotiations between his lawyers and the city's attorneys. Eventually, a settlement was reached and by September 2022, Camacho's attorney instructed him to pick up the records.

The files were delivered by the city on a flash drive (purchased by Camacho himself) with a database of more than 9,300 LAPD officers, an attached paper roster, and a letter from the city attorney. "The letter from the City Attorney essentially said, this satisfies our agreement per the court and we have redacted undercover officers from these photos,” said Camacho.

Things were mostly silent until late March of 2023 when an independent activist coalition called ‘Stop LAPD Spying’ launched watchthewatchers.net. The site is described as a “community resource that indexes LAPD’s official records of its officers, all of which LAPD made public through California Public Records Act requests.”

The coalition had previously contacted Camacho to request access to the records he had obtained. Unaware that sharing the information would pose any issues, Camacho released the public record database to Stop LAPD Spying. “At this point, they were public records,” says Camacho of his decision, “I’m no gatekeeper, so if a community organization wants access I’m going to give it to them.”

The public had mixed reactions to the launch of the Watch The Watchers website. Police accountability has been a significant issue in Los Angeles, as many people believe that the city has not done enough to hold police accountable for their misconduct. Many online users praised Stop LAPD Spying for taking steps to develop transparency tools intended for public use.

The release of public records, however, also evoked negative responses from the LAPD and other pro-police advocates, who claimed that the files released included identification for several undercover cops. The Los Angeles Police Protective League, a police union representing over 9,000 LAPD officers, filed a sweeping misconduct and negligence complaint against now-retired Chief of Police Michel Moore. The union’s director, Jamie McBride, also mischaracterized the legally obtained records as a "leak" and referred to the release of LAPD officers' names and information as "reckless" in an interview with Fox News.

In April 2023, the Los Angeles City Attorney's Office filed a lawsuit against Ben Camacho and the "Stop LAPD Spying Coalition" in response to the backlash they received from police advocates. The city alleged that they had attempted to obtain files that “inadvertently” included the pictures and names of undercover LAPD officers, despite explicitly stating otherwise in the letter addressed to Camacho from the City Attorney. The lawsuit asked that a judge of the LA Superior Court order Camacho and members of the coalition to return the files obtained through the California Public Records Act request and have them destroyed.

In response, Camacho and the Stop LAPD Spying coalition filed anti-SLAPP motions to dismiss the city of LA's lawsuit against them. Camacho told CALÓ News that the lawsuit impedes his ability to do his job as a reporter. “The lawsuit against me and the coalition is an attempt to use the court to stop someone or something from exerting their rights as a person or entity,” Camacho stated. “In my case, being a journalist and reporting on something newsworthy [and] in the coalition's case, freedom of speech.”

The Office of L.A. Mayor Karen Bass has stated that they are unable to comment on pending lawsuit against Camacho. Photo Credit: Mario Tama/Getty Images

During Camacho's first court hearing, the judge reviewed a temporary restraining order that the city attempted to issue. The order would have prohibited Camacho and the StopLAPSpying Coalition from distributing photos obtained through the city. However, the judge ruled in favor of Camacho and the coalition, allowing them to continue distributing the photos.

The courts were also tasked with determining whether the photos in question were the property of the city and if Camacho was wrongfully in possession of them. The city however failed to provide sufficient evidence that undercover officers were included in the release of photos, as the LAPPL and city officials were at odds over what defines "undercover."

"it is not entirely clear how LAPD defines officers acting in an undercover capacity," Los Angeles County Superior Court Judge Mitchell L. Beckloff wrote.

Recently the LA City Attorney filed a second lawsuit against Camacho and the Stop LAPD Spying Coalition. It seeks to hold the defendants financially responsible for the damages claimed in the negligence class-action suit.

Camacho believes this is an attempt to intimidate him, an effort he alleges is being led by Los Angeles City Attorney Hydee Feldstein Soto with the support of Los Angeles Mayor, Karen Bass. “Naming me [in the lawsuit] and not Knock L.A. is a form of intimidation,” Camacho said. “Going after a local journalist of color is trying to make a statement that the city of LA does not support a free press. The city of LA does not support local reporting or local investigative reporting. And the city of LA is vehemently opposed to police accountability reporting.”

CALÓ News reached out to The Office of L.A. Mayor Karen Bass about Camacho’s claims, to which they responded that they were “unable to comment on pending litigation.”

Since the first lawsuit was filed, many newsrooms have spoken out in defense of Camacho. The Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press and 21 news organizations urged a California court to deny the city of Los Angeles’s “attempt to force a local journalist and community advocacy group to return and/or destroy lawfully obtained police records,” in an amicus brief submitted by a national media coalition.

The brief emphasized the importance of ensuring that journalists and news organizations remain free from “unconstitutional restrictions” on their ability to gather and publish newsworthy information for the benefit of the public.

Free-speech advocates fear the outcome could have far-reaching consequences for the future of journalism and potentially pose a significant threat to the “news gathering rights of journalists.” Similarly, Camacho is worried that the city’s actions could discourage reporters from pursuing stories that are in the public interest, which he believes is ultimately the public's right to have access to public information.

“The entire idea behind the lawsuits is so dangerous because it would mean that the government can claim privacy or confidentiality on public records,” Camacho said.

(0) comments

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

Keep it Clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexually-oriented language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't Threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be Truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be Nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be Proactive. Use the 'Report' link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with Us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.